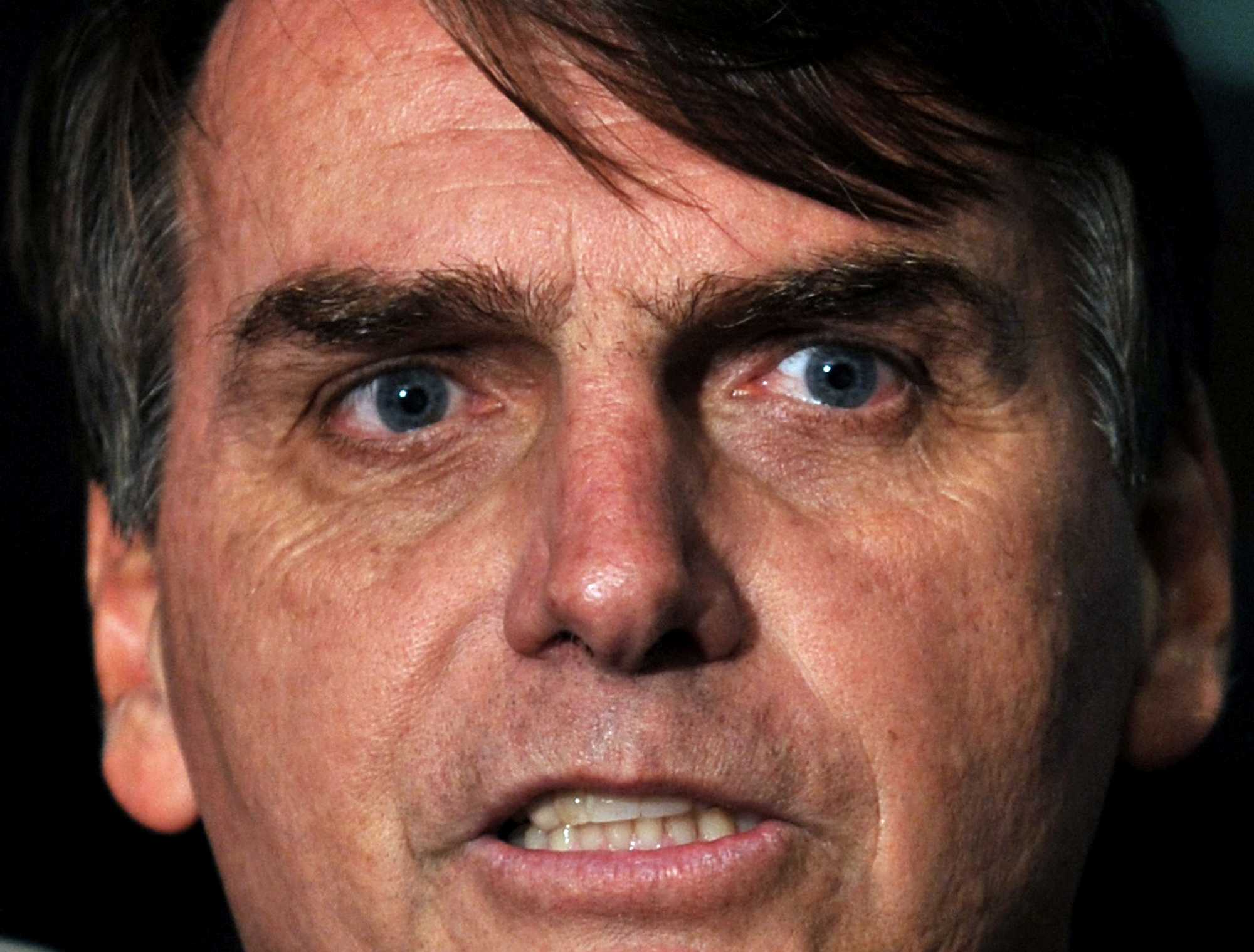

On April 4, Christian Social Party congressman Jair Messias Bolsonaro gave a racially charged speech at the Hebraica Club in Rio de Janeiro. The speech made headline news, but it is just another stone paving the path of controversies that describe his political career.

During his speech before some 500 people, he claimed that people living in reservations were “parasites”, that quilombolas (black community members, descendants of runaway slaves) “weren’t even fit for breeding”, that NGOs and social movements were stealing the country’s resources, and that the only way to fight crime was handing out guns to the population.

Under him as president, the pre-candidate claimed – presidential elections in Brazil are due next year -, there would be zero land space for reservations, zero funds for NGOs and social movements, and a gun in each house to “fight the bad guys” – meaning members of the Land Reform Movement (MST), among others.

Bolsonaro later pretended to defend himself in a YouTube video, in which he again claimed that natives and quilombolas were draining national resources. This time, however, he went even further, stating that Funai (the National Indigenous Foundation) deliberately chose the “richest and most fertile” lands to “give away” to “Indians and blacks”, while stealing land from whites who had been “living there for centuries”.

Hosted by the Hebraica Club society, Bolsonaro’s April speech sparked much debate. Fernando Lottenberg, president of the Brazilian Israelite Confederacy, called the event “a mistake”, and protesters questioned the Jewish club’s invitation of a far right leader known for his ties with neo-Nazi movements: in 2015, he was in the news for supporting Professor Marco Antônio, a well-known Nazi sympathizer who showed up at a Human Rights commission hearing dressed up as Adolph Hitler.

In the same year, Bolsonaro gave his support to – and was in turn supported by – skinhead groups, who were openly asking why is it legal to have a Communist Party in Brazil, but not a Nazi one. A self-confessed “admirer” of Hitler, he and two of his sons, Carlos and Flávio Bolsonaro – both politicians – openly support eugenics.

According to Bolsonaro, since Brazil is “a Christian country”, non-Christians should stay out of political life – as they are not “true citizens”. Islam and African religions should be banned, as they are antithetical to the “national faith” and operate as an “open door to terrorists”. Jews, on the other hand, “are Christians”.

The speech at the Hebraica Club has earned him two lawsuits presented by the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), the Workers’ Party (PT), and the National Coordination of the Black Quilombola Communities (Conaq), and sparked protests by Jewish groups, who gathered outside the club. These simply added up to the long list of lawsuits and protests that Bolsonaro has managed to attract in 26 years of political life.

A History of Controversy

Bolsonaro, a former Army captain, is well known for his “controversial” opinions since the very start of his political career, following his arrest in 1986 for planning to bomb a pipeline and army barracks in Rio de Janeiro.

Among his many controversial statements, Bolsonaro is widely remembered for claiming that “the only reason he didn’t rape” a congresswoman was “because she didn’t deserve it” – he later explained that she didn’t deserve it because “she was too ugly”-; for saying that President Fernando Henrique Cardoso should be “shot in a public square”; for calling black activists “animals” that should “go back to the zoo”; for stating that homosexuality is due to “not enough beatings”; and for confessing that he “didn’t have to worry” about any of his children dating afro-descendent women or being gay “because he gave them a proper education”.

To him, Haitian, African and Middle Eastern refugees in Brazil are “the scum of humanity” and should be dealt with “by the army”.

One of the staunchest defenders of the late Brazilian military dictatorship and of the often violent actions of the current military police, some of his heaviest claims relate to the shady 1964-1985 period. The coup d’état in 1964 was, according to him, “a revolution”, and praises Carlos Brilhante Ustra, the most infamous of all Brazilian torturers of the 21 year long military regime, as one of the country’s greatest heroes.

In his view, the dictatorship’s mistake was not using torture, but failing to kill off “the Commies”. During a Truth Commission hearing on people who “disappeared” during the dictatorship, Bolsonaro declared that only “dogs look for bones”.

Coherently, Bolsonaro defends modern-day violence as well as the other Latin American military regimes of the recent past. Pinochet’s mistake was not killing enough people, he said back in 1998. He also said that police, who shot 111 prisoners at the Carandiru detention facility in 1992, “should’ve killed 1.000”.

Considered by Amnesty International as the most violent police force in the world, responsible for 15,6% of the 54.000 violent deaths per year in the country, the Brazilian Military Police is deemed “too soft” by Bolsonaro, and should be “killing more”, while human rights NGOs are “a bunch of scumbags and morons” which he vows to “ban from the country”.

The brunt of his hate speech, however, goes against the LGBT community: in an interview with Playboy Magazine, he said that he would rather see his sons die in an accident than have one of them “show up with some moustached guy”, and that if he saw “two guys holding hands” in the street he would “beat them up”.

In another 2014 interview, he maintained that homosexuals “should bow down” before the majority. And yet in another interview in 2013, he claimed that “90% of the kids adopted by LGBT couples” would be used as sex slaves – hence, the legalization of same-sex marriages “would legalize child abuse”. The list goes on.

British comedian and documentary producer Stephen Fry dealt with Bolsonaro and his hateful views in his 2013 documentary Out There. Fry, who interviewed Bolsonaro, thinks that he is “typical of homophobes I met all over the world, with their mantra that gays are out to take over society”.

Actress and activist Ellen Page also interviewed Bolsonaro, in 2016, in her documentary series Gaycation: Bolsonaro claimed this time that homosexuality was caused by women accessing the workforce and by the use of drugs, before going on to say that people like Page “need a violent corrective” and comparing gays to criminals.

“The Myth” and His Followers

Despite it all – or perhaps because of it – Bolsonaro is one of the most popular political figures in Brazil. His fans call him “the Myth” and his popular support is growing steadily – and fast. From a 6,5% voter intention last October, Bolsonaro reached 13,7% in February – second only to former president Luís Inácio Lula da Silva. But while Lula, with a 30,8% voter intention, is in a slow decline, Bolsonaro keeps on rising.

On Facebook, the most popular social media in Brazil, Bolsonaro has over 4 million followers – more than Lula, with 2,8 million, yet somewhat less than former presidential candidate and current senator Aécio Neves (Brazilian Social Democratic Party – PSDB), who has 4,3 million. But even though Bolsonaro has been a federal congressman for more than 26 years – he is now in his seventh term of service – most of his followers see him – unlike Neves – as an outsider from traditional politics.

His ascent follows a well-known pattern, common to other rightwing populist – including US president Donald Trump. Previously seen as something of a joke, Bolsonaro has risen to prominence by connecting with voters who do not feel represented by any of the other candidates, attracted by what they perceive is his “sincerity” and “bravery” at “saying things as they are”.

Much like Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, Marine Le Pen in France, Nigel Farage in the UK, and Trump in the US, the driver of Bolsonaro’s campaign is an alleged threat against “national identity”. While the aforementioned point to an external threat – immigration – Bolsonaro adds several internal ones – native peoples’ reservations, Communism and “gays” – and promises to do away with the old, corrupt political structure.

He is closest to president Trump, though, in that both show no restraint in saying what they think – no matter how offensive or counterfactual. During his speech at the Hebraica Club, Bolsonaro insisted that he did not “say things to please”. Resonating with a large part of the electorate, the same bold claims that make him so controversial also make him popular, in particular with young people: 20,4% of the 16-24 age group are currently supporting him.

These young followers – derisively called “Bolsominions” by the Left – have strong ties with the Brazilian alt-right. Most of them are pro guns, anti-immigration and fiercely homophobic. Ultra conservative Facebook pages such as Orgulho Hetero, Faca na Caveira and Politicamente Incorreta are helping the build-up of “the Myth”, and on Whatsapp, Bolsonaro’s claims are posted out of context, and spread rapidly due to their alarmist tone.

Most Bolsonaro supporters praise him because “he fights against political correctness” and “immorality”. Some support him for his pro-gun stance. Much like Trump, Bolsonaro has the unwavering support of a young population who believe their rights and “rightful place” are being taken over by minorities and “political correctness”.

However, unlike Trump – most of whose support came from low income and low education segments of society – Bolsonaro enjoys much support from higher education students, particularly from the most traditional university faculties such as Law, Engineering and Medicine, who believe that “their” place in society is being stolen from them by “Communists” and through “affirmative action”.

Both uneducated and educated Bolsonaro’s voters view all other candidates as “Communists” and traitors. Beyond the economy, healthcare and violence, they prioritize “cultural war” against those they perceive as enemies of the state: feminism, political correctness, racial movements, LGBT, non-Christian religions, immigrants and “bandits” – and this makes a change of allegiances on their part highly unlikely.

Being one of the few high-profile congressmen unaffected by the ongoing Lava Jato investigation – on bribes to politicians by major contractors such as construction giant Odebrecht – and the multiple whistleblowers involved, Bolsonaro adds another asset to his campaign: the claim that he is an exception to the widespread corruption of the Brazilian Congress – thus reinforcing his image as a political outsider.

He ran for Speaker of the House and got only 4 votes out of a total of 513, but managed to turn this result to his advantage saying that it showed that “they” don’t want him – as do the recent lawsuits against him, which he presents as attempts by “traditional politics” to silence him.

So far, his demagoguery is working. But it remains to be seen if he will manage to keep the momentum right up to the 2018 elections – especially after his party, unlike Bolsonaro himself, has been shown to be involved in the Lava Jato scandal – or if, in the end, his campaign will fizzle just as Geert Wilders’s did.

Pedro Henrique Leal is a freelance journalist and a human rights activist in Brazil. He writes for the independent websites À Margem and Coletivo Metranca, as well as Jaraguá do Sul newspaper O Correio do Povo.

This article appeared originally in https://www.opendemocracy.net/