From a cartoon about child workers to an HBO mini series, Brazil is turning to television and social media to shed light on modern slavery and change attitudes through entertainment.

Prosecutors and judges are spending funds – seized from those who profit from modern slavery – on documentaries and movies in a drive to spark debate, engage with more people and bring to life the reality of slave labor in Brazil.

“Public opinion is fundamental,” said prosecutor Luiz Carlos Fabre, who brokered a deal between a production company and the Labor Prosecutor’s Office to part fund a series about slave labor for a major regional broadcaster, HBO Latin America.

“These issues need to be in the spotlight always,” said Fabre, whose office provided about 200,000 reais (US$ 53,100) for the upcoming series, which has yet to be given a release date.

With more than 40 million people enslaved worldwide, the entertainment industry has made a host of documentaries and films that explore life as a modern slave. But it is unorthodox for a government to commission content and detractors question the value of funding entertainment to educate.

Under Brazilian law, civil fines for labor violations and court convictions relating to public issues should be awarded to the victims or spent on helping the affected community.

Prosecutors and judges decide how to spend the funds, and have committed tens of thousands of dollars in recent years to anti-slavery screenplays.

A short cartoon on the dangers of child labor was screened last month at a fair in Juina, a small city in Mato Grosso state – a region where prosecutors say child workers are not seen as a problem by the public. It was also shared across social media.

“We heard people say: better (for a child) to be working, than on the streets doing nothing,” said prosecutor Ludmila Pereira Araújo, so she used 92,000 reais (US$ 23,256) in labor fines to produce the cartoon, adapted from a comic book series.

“We made it to try and reach younger people that use social media heavily,” Araújo said.

Money No Object

Money gained through fines and court convictions has been used by prosecutors and judges to build hospital wings and immigrant centers, buy equipment for labor inspectors, and fund social enterprises that aim to do business and do good.

Yet a lack of spending guidelines worries some civil servants.

Jonatas Andrade, a judge with more than a decade of experience working in the state of Pará, said he felt more and more uneasy as the stash of money he managed kept growing.

“It would be pretentious on my part … to presume to know where to best spend it,” said Andrade, who consults with state officials and anti-slavery campaigners on how to use the money.

In 2015, he allocated 1 million reais (US$ 252,786) to fund the film “Pureza” – a real-life account of anti-slavery activist Pureza Lopes, who traveled Brazil in search of her son after learning that he had been enslaved on a farm in the rainforest.

The movie will be shown at international film festivals and in Brazilian cinemas over the next two years, according to Andrade, who said he hoped it would raise awareness.

In Brazil – whose government has rescued more than 53,000 people in slave-like conditions since 1995 – slavery is defined as forced labor, and also includes debt bondage, degrading work conditions and long hours that pose a health risk to workers.

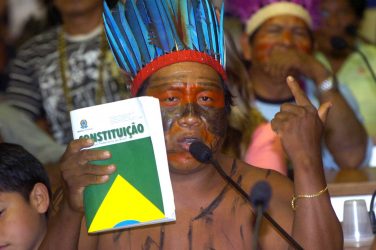

President Jair Bolsonaro, who took office on a populist campaign targeting the opposition’s corruption and economic ineptitude, last month criticized Brazil’s labor laws and said the definition of slave labor “terrorized” bosses.

Screenplays with a message can be ineffectual without good planning and appropriate screenings, be it in schools, labor unions or regions rife with slavery, said Fred Lucio of ESPM Social, a consultancy promoting corporate social responsibility.

Otherwise, the film might win awards but touch nobody.

“Many times the government gives money…and has no further involvement,” said Lucio. “Then it’s just throwing public funds to waste.”

This article was produced by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Visit them at http://www.thisisplace.org