Tristeza não tem fim

Felicidade, sim

Vinicius de Moraes, Antonio Carlos Jobim

The beginning of June saw the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) reach its twenty-seventh installment. Already one of the most important business summits in the world, this was doubtless its most significant version. With a spotlight on new investment policies for qualitative as well as quantitative growth, the central theme of the event was “The Foundations of a Multipolar World”. While meant to crown President Vladimir Putin’s re-election to another term in office, the real guest of honor was Russia’s unexpected growth and economic transformation. Taking part in the opening festivities was Brazil’s former-President Dilma Rousseff, now head of the New Development Bank (a.k.a. the “BRICS” Bank).

A key backstage front-and-center player between Brazilian and Russian officials was journalist Pepe Escobar, a man who knows no geopolitical boundaries. It was none other than Mr. Escobar who reported that high-level meetings were subsequently held between Ms. Rousseff and Dr. Sergei Glazyev, chairman of the Eurasian Economic Commission (EEC). Ms. Rousseff also met with President Putin himself to discuss monetary options for a dollar-dominated world. The SPIEF shone through the windows of an edifice to which the rules-based international order has tried to seal the doors.

ON THE BANKS OF THE NEVA

Pepe Escobar has been one of the most important promoters and popularizers of multipolarity within independent news media. Embodying multipolar emergence itself was the SPIEF, as it hosted over 20 thousand delegates from one hundred and thirty-nine countries. Forever on par with the innovators, Mr. Escobar is also part of the conversation. He aims for a more accurate moniker, whether it be “polycentric multinodality” or President Putin’s suggested term of “a harmonic multipolar world”.

In a move to shame organizers of the Davos World Economic Forum or the off-limits Bilderberg meetings, the SPIEF held an open and transparent study session on “Philosophy and Geopolitics in a Multipolar World”. Heading the Organization Committee was the esteemed Russian philosopher, Dr. Alexandre Dugin. Surely as a sign of the trust he has secured within the Russian intelligentsia, Mr. Escobar was invited to sit among the panel’s distinguished guest speakers.

Dr. Dugin selected voices on multipolarity to bridge over differences far greater than those separating the NATO culture from Eastern European civilizations. To this end, he was joined by Dr. Maria Zakharova, Director of the Department of Information and the Press of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. She spoke with passion about the philosophic dimensions of Russia’s 2023 Foreign Policy Declaration, while closing her talk with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s oration on the Russian soul.

Next to speak was distinguished Chinese philosopher Zhang Weiwei, from Fudan University. He spoke to how Chinese philosophy lifts its normative principles to converge with practice, whether through testing, validating, or policy project planning. According to Dr. Weiwei, the Chinese philosophical vision surpasses the “outdated, unjust unipolar world order” with a more equitable and humane planetary prospect. He emphasized the importance of centralized state planning as behind the success of the People’s Republic of China’s flight from colonialist humiliation to unprecedented prosperity. Unlike in the West, the government protects its population from private-bank debt-producing instruments by a glass dome of national public trusts. The PRC has also achieved leadership with its clean energy technologies, thereby offering healthy living conditions for its vast population.

Then came Mr. Nkosi Zwelivelile Mandela. In addition to Chairing the International Russophile Movement, he is Member of the Parliament of South Africa, heading the Portfolio Committee on Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development. Mr. Mandela recalled his father, the great Nelson’s unfinished legacy of ending legal and social settler-colonialist apartheid. South Africa’s struggle today, he emphasized, is to bar IMF-funded financial institutions and large hands with sticky fingers as they threaten to instill apartheid by economic means. Following his profound words, Ms. Zeinab Al Saffar, Lebanese media presenter and analyst, evoked how the meaning of multipolarity itself represents a promise for Palestinians to execute their right to return to their own land.

Meanwhile, Mr. Konstantin Malofeev spoke enthusiastically of the care given to Russian culture, arts, and higher education by the current leadership. Mr. Atul Aneja from India lent his views on provincializing the G7, while members of the public resoundingly added their considerations on multipolarity. Philosophy with a geopolitical flair proved itself the foolproof pipeline by which to convey peace and prosperity through multiplicity.

BRAZILIAN JOURNALISM AS IT CAN BE

For readers still unfamiliar with Pepe Escobar’s writings and podcasts, they represent nothing less than hope for a profession that long ago became a synonym for manufacturing public opinion and consent. Few other professions have been so brutally compromised and corrupted as journalism. It has become the medium by which to advance the interests of financial capitalism. In moments of crisis, its veneer has been seen to shatter. Examples pile up in mounds, be it with the political climate disaster in southern Brazil, where the monopolistic news outlet Zero Hora justified the rabid privatizations undertaken by the State and municipal administrations, damning millions of citizens to massive flooding. Or, take the once laudable French journalist medium, now soldered to the billionaires’ president Emmanuel Macron, marshalling the extreme-right to ward off working-class discontent.

The media is no longer the message, but the conduct. From the cool “massage” of the 1960s, the contemporary oligarchic concentration of media outlets burns through skin and spirit. Its heated stimuli propel viewers into fits of hysteria—or rampages of rage. To be sure, journalism can be an exciting profession due to the diversified opportunities it offers. At best, the penalty for seeking the truth is unemployment. About those, such as Julian Assange, Gonzalo Lira and the dozens of reporters slaughtered in the Donbass and Gaza, the news is less fit to print.

Through self-censorship, journalism embodies freedom of speech squeezed into silence. Rarely does the grip grow as strong as when the conveyers of critical historical knowledge dare to appear on the studio set. In their struggle against academics and intellectuals, the corporate “editocracies” have even trained their professionals to abandon all protocol as they morph into hitmen and snipers of the word instead.

Then there is journalism with a fuzzy J, one of its most illustrious embodiments being Pepe Escobar himself. Hailing from São Paulo, Escobar has been a pioneer in digital alternative media, covering the arts and the arcane for decades. At odds with hometown academics in an arms race to set musical trends, he opted instead to test his chops in the geopolitical framework. It was a time when the West compensated for the destruction of its opposition parties with trance-inducing canticles to post-national European sovereignty set against a break beat spun by NATO. Escobar’s name began circulating internationally shortly before 9/11. Along with a handful of luminaries like the late Robert Fisk, he journeyed into the mountains of northern Pakistan and Afghanistan to provide real reporting. By then, the overwhelming majority of outlets had already forgone compliance with best practices by merely channeling dispatches sent from Paris, London, and Cairo on events taking place in Central Asia.

As the War Party strengthened its hold on American politics under former President Obama, Escobar ventured into conceptual forays to which few, apart from Noam Chomsky, had access. After the Workers’ Party snatched the presidency in Brazil in 2002, he saw the future in Lula da Silva’s endorsement of the newly formed international economic organization called BRICS. At the turn of the century, Brazil’s nominal GDP was astonishingly at par with China’s. Today, it is one ninth of its size even in purchasing power parity. As evidence of how the Washington Consensus has always impeded the development of its imperial backyards, the setbacks suffered by Brazil’s national industry since the 2016 congressional coup could be accepted into evidence in a court of law.

Since the 2014 Maidan Coup and the intensification of the Kiev regime’s bombardment of Donbass through the fall of 2021, Escobar managed to maintain his nomadic circulation to provide the other vantage point. Through his art, the news functions to not only inform, but teach. A polyglot with extensive readings, Escobar incarnates what corporate boards seek to weed out. Faced with his tips and scoops, the Tucker Carlsons of the world keep on fuming, despite the fortunes amassed via their Deep State insiders.

Nor does Escobar have a need to adorn his political proclivities. This is rare in a profession seemingly unable to live without brandishing them. Given the content of the news he brings, party politics are irrelevant. Making the political is what counts. Post-colonial before the term was circulating, the viewpoints he gives North Atlantic audiences, were they only to listen, underscore his ethical commitment to global prosperity and the end of financial rule by the City-controlled Central Banking junta. Such news might not paint the prettiest of pictures for the convictions perpetuated by the “West”. He compensates for it though with Kabuli and whirling dervishes. His journalistic elixir brews an antidote for the kind of ideas that just might revert NATO’s drive toward direct conflict with Russia and China.

Multipolarity, or multinodality, arises as a cognitive framework through which to filter the geopolitical narrative. This is what history achieves when it pumps from archives and splits from journalism. Besides, Francis Fukuyama’s version of the dissolution of the Soviet Union has been hammered into so many heads that few even realize how Russia’s economic collapse was not the result of Soviet mismanagement. Although plummeting in an economic crisis during the 1980s, Russia and Ukraine only crashed into collapse due to Wall Street’s shock doctrine circa 1993. One might take solace in Jeffrey Sachs expressing his mea culpa today over his role in that travesty. Still, his admission proves how the combined West never repealed its settler-colonialist scope from the tremendous wealth in resources buried beyond the Soviet border. From Bonaparte to the British, from the WWI-Allies to Nazi-Germany, and once again through the current proxy war, imperial expansion has never been limited to a southwardly pounce.

CULTURAL GRANDEUR NOT WITHHELD

With War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy propelled Russia into the literary absolute. By extending his already monumental narrative to geostrategic considerations, he lectured Europeans on how the rhythms of history slip from the will of its framers. Multipolarity has emerged from the non-apparent. Typical to its structure, it moves through differential patterns. At times, it ascends with gradual steps, while at others it subsides into pauses of punctuated equilibrium. After trade sanctions were launched against the Russian Federation in 2015, multipolarity has sped up in quite unexpected ways.

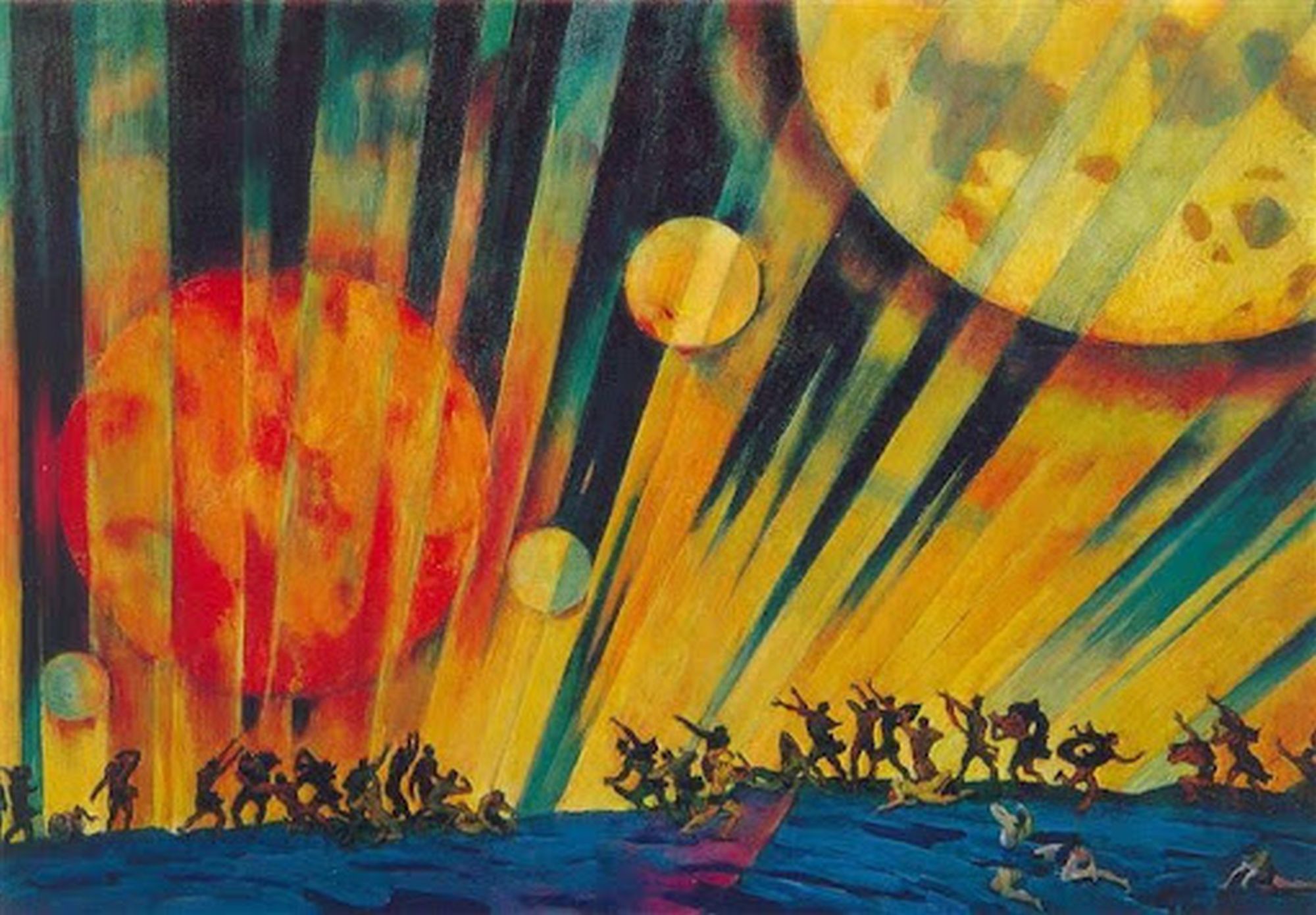

Back at the SPIEF Philosophy and Geopolitics Panel, the implications of this ascent were evoked by Escobar through a longue durée take on ethics and memory. With Dr. Dugin granting him the final word, Escobar stretched out in his signature nomadic style to evoke the Danube, on the banks of which Marcus Aurelius stood schematizing the principles of stoicism. Escobar then took flight to the flow of the Neva in another SP. As testimony to the residents of the city formerly called Leningrad, he evoked the eightieth anniversary of its liberation from the Germans. As part of a plan to exterminate its population through starvation, the Germans blockaded the city from late 1941 to 1944. In this most cultural and proletarian of Russian cities, well over one million civilians starved to death as a result. Eighty percent of German armed forces with their Eastern European fascist allies were deployed to destroy the Soviet Union’s greatest cities. The barbarous objectives behind the blockage makes it plain how World War II must also be read as the perpetuation of Western settler colonialism, with the recourse to slave labor as its end. Just as it also should be a reminder of how before 1942, Nazi Germany was an American partner—as it would later become once again.

In those years, Leningrad/St. Petersburg was also the setting for the composition and performance of one of the greatest symphonies ever written. The Soviet Union’s composer of genius, Dimitri Shostakovich, wrote his masterwork Symphony No. 7 amidst the siege. In March 1942, starving musicians of the Leningrad Radio Orchestra battling on the city’s defensive lines were summoned along with army regulars to prepare its performance as the jewel of Russia faced obliteration from Luftwaffe bombings. Western classical music critics have failed miserably to appreciate Shostakovich’s oeuvre. Unable to surmount their own indoctrination, these critics fumigate through McCarthyist double standards in disbelief that the twentieth century’s greatest composer could have been a proud communist.

Shostakovich stands as the true composer of proletarian revolution, his name adorned repeatedly with the highest honors bestowed by the Soviet Union. A cultural primer on greater Russia would do well to insist upon listening to Valery Gergiev’s rendering of Shostakovich’s Symphonies Nos. 5-12, or revel into Sviatoslav Richter and Mstislav Rostropovitch’s performances of his chamber works, before disintegrating into Kazemir Malevich’s Black on Black. After War and Peace has emboldened one’s conviction that truth is to be found beyond the Dnieper, plunge again, cleansed, into Elem Klimov’s 1985 Come and See. Paced by Oleg Yanchenko’s soundtrack, the film will make you frontally dissolve into Germany’s other genocide: the firebombing of hundreds of Belarusian villages and extermination of their inhabitants. Adagio lamentoso (and don’t forget to invite Justin Trudeau).

Meanwhile at the SPIEF panel, the hour was to celebrate the Russian mind. Dr. Dugin exalted the country’s renewed spirit after recovering from the Wall Street/IMF onslaught of the 1990s. No matter how one represents the Soviet Union, the fact is that it held the second position in nominal GDP for thirty years. It was the first country to put a man into space, while inventing science fiction along the way. In his SPIEF plenary address, President Putin committed to creating no less than twenty-four new universities by 2030, while his government shifts toward policies of “structural change” oddly evocative of the PRC’s central planning. Indeed, as Dr. Weiwei recalled, long-term project planning is yet another Soviet innovation from which China has learned greatly.

With his endeavors to carve out recognition of Russia’s rightful place in European philosophy and geopolitics, Dr. Dugin could not have fared better. As for Pepe Escobar, the art of journalism owes him the rock of his courage and the roll of his commitment.

Norman Madarasz is Professor of Political and Economic Philosophy at PUC-RS (Porto Alegre, Brazil).