Former Brazilian billionaire Eike Batista was arrested upon arrival at the Tom Jobim/Galeão International Airport, in Rio de Janeiro, by Federal Police officers. He was arriving from New York where he had gone on business.

Batista had been placed on Interpol’s list as an international fugitive. He was checked at the Medical Examiner’s Office (IML), in Rio, for his health condition and then sent to the Ary Franco prison in Rio de Janeiro.

The entrepreneur, who is the owner of the EBX group, is suspected of money laundering in a corruption scandal that has also ensnared former Rio de Janeiro state governor Sérgio Cabral, who is already jailed.

Batista’s arrest warrant was issued last week as part of the Federal Police’s Operation “Efficiency”, a spin-off case originating from the “Car Wash” probe.

Not long ago Eike Batista was considered one of the world considered one of the world’s 10 richest people. Brazilian federal police detained Batista on allegations of bribing the former governor of Rio, as part of the country’s largest investigation into a corruption scheme in the state-run oil company Petrobras.

The police had raided his home on Thursday. He argued that he never intended to flee the country. Batista declined to answer a reporters’ question about whether he considered himself guilty or innocent.

“I am returning to answer to the courts, as is my duty,” Batista told the Globo television network at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. “It’s time for me to clear this up.”

Police accuse Batista of paying US$ 16 million to former Rio governor Sergio Cabral in exchange for support of the businessman’s many Rio-based endeavors.

The 60-year-old businessman, who has sold his stakes in the energy, mining and logistics empire known as EBX Group, was once married to actress and Carnaval queen Luma de Oliveira and is the son of a former chief executive officer of mining company Vale SA, one of the companies involved in the Samarco mining disaster, a dam collapse in 2015 that killed 19 people and spread pollution and devastation through a vast area.

“I think federal prosecutors are cleaning up Brazil in a fantastic manner,” Batista told Globo TV. “The Brazil that is being born now will be different.”

Five years ago, he had a net worth exceeding US$ 30 billion and was considered one of the world’s 10 richest people.

https://youtu.be/6YfnrUgIovs

Odebrecht

In another important corruption case, federal Supreme Court President Cármen Lúcia approved Monday plea bargain statements of 77 executives and former employees of Odebrecht, Brazil’s largest construction conglomerate, in which they detail the corruption network run inside Petrobras, the country’s state-run oil company.

As a result, the more than 800 testimonials have become valid and will be used as evidence.

The sweeping corruption investigation, which now covers several state-run companies, has jailed prestigious CEOs and major political figures, convicted more than 80 people and confirmed some US$ 2 billion in bribes paid over several years.

The records include the testimony of the company’s former CEO, Marcelo Odebrecht, who has been jailed in Curitiba since 2015 and has already been sentenced to 19 years in prison by a lower federal court.

It is now largely speculated whether Cármen Lúcia will declassify the contents of the testimonies where former executives have implicated dozens of politicians who are currently in office.

The top court’s green lights for the testimonies came after the death on January 19 of Teori Zavascki, the Supreme Court justice overseeing the Car Wash case at the Supreme Court level.

A plane he was flying in fell into the sea near Paraty, Rio de Janeiro. He had interrupted his judiciary Christmas holidays to ensure he could authorize the testimonies into the case as quickly as possible.

Upon Zavascki’s death, Cármen Lúcia, as the chief justice of the Supreme Court, gained the authority to accept the testimonies during the judiciary Christmas break.

But after the holidays end, which will happen this 31 of January, Cármen Lúcia will lose her authority to decide on Car Wash matters, and another justice should take over oversight of the case at the Supreme Court.

The decision as to who is going to be the next reporting justice on the case is still under speculation at the Supreme Court – under the internal regulations of the court, there can be a number of outcomes.

It is not known, for example, whether the next justice in charge of Car Wash will be drawn from among the full bar or the so-called “second panel”, a smaller chamber of justices within the bar Zavascki was part of.

Bribery Department

According to Federal Police investigations authorized by Federal Judge Sérgio Moro of the lower court in Curitiba, Odebrecht had maintained an informal department within its organization that was responsible for kickback payments, known as the Structured Operations Division.

According to the Car Wash task force, part of the company’s employees were dedicated to operating these payments, which were directly assigned by the company’s senior management.

The transactions were logged into a sophisticated computer system with servers in Switzerland, whose content the Federal Prosecution Service is still taking steps to gain access to, due to the system’s strict security protocols.

Last March, Federal Police seized a spreadsheet at the home of former Odebrecht executive Benedicto Barbosa da Silva Júnior, as part of Operation “Acarajé”, as the 23rd stage of Operation Car Wash was dubbed. The spreadsheet, which was classified, listed payments to more than 200 politicians.

The company’s illegal dealings reached beyond Brazilian borders. Odebrecht is investigated in at least three other Latin American countries: Peru, Venezuela and Ecuador.

As part of a corporate leniency deal with the United States in late December, the company admitted to paying US$ 3.3 billion in kickbacks to government officials of 12 countries.

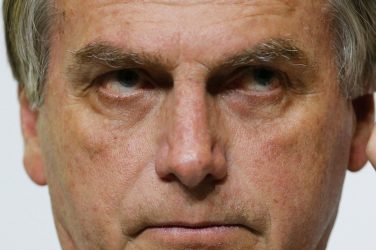

Brazilian President Michel Temer commented that the Chief Justice did right by authorizing the use of the plea bargain statements of 77 executives and former employees of Odebrecht construction company.

“I think she did what she had to do and, in that sense, she did right,” Temer said while visiting the state of Pernambuco.

The president made the remarks after attending the inauguration of the third water pumping station as part of the São Francisco River Integration Project, in the town of Floresta, in Pernambuco.

ABr/teleSUR