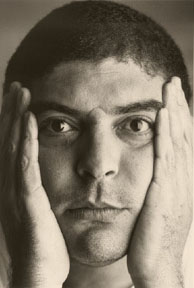

Marcos Sacramento is creating new samba hybrids.

Marcos Sacramento is breathing new life into old sambas.

He’s a voyager who gazes forward and backward at the same time.

And the voice—that glorious voice!

Perhaps the voice should be our point of departure.

Perhaps the voice should be our point of departure.

Once there was Orlando Silva, who for seven magical years between 1935 and 1942 was The Ideal Singer. He possessed a clear, beautiful tenor voice that never erred, high or low, and was capable of interpreting to perfection any style of song, be it samba, waltz, or choro. Orlando had no peer. Then the voice went, and no other replaced it. Brazil has always boasted an overabundance of wonderful singers—still does. But perfect voices are rarer than rain in the sertão.

More than fifty years after Orlando Silva, there’s another perfect voice in Brazil, and more specifically in Rio, for Marcos Sacramento is a consummate carioca. Like Orlando Silva, Sacramento possesses a clear, beautiful tenor voice that never errs, high or low. It is a voice of a thousand nuances, at once cool and warm, seductive and swinging, relaxed and precise, mellifluous and meticulous. A voice that captivates and entraps and commands a permanent place in your head, heart, and musical universe.

Like Orlando Silva, Marcos Sacramento is capable of interpreting to perfection any style of song, be it samba, waltz, or choro—he even played the role of Orlando Silva and sang Orlando’s hits in the TV series Kananga do Japão (he sings “Rosa” by Pixinguinha in the video below). But Sacramento doesn’t stop there; he’s been known to make forays into experimental rock, blues, and rap, among other genres. The twist is that Sacramento’s rap and rock are firmly rooted in samba. And lest we evoke images of Brock and hit-parade pagode, let’s clarify at the outset that Sacramento’s music is light years away from the interchangeable offerings of me-too bands that flood Brazilian airwaves from dusk to dawn.

Guanabeat

Not too long ago, the journalist João Máximo was reported to have said that samba is a used-up genre with few opportunities left for innovation. Marcos Sacramento is proving otherwise. His latest solo disc, Caracane (Dabliú DB 0052; 1998), has plenty of new things to say, both musically and lyrically.

Caracane is another name for Cara de Cão, or Dog Face Hill, located just below Sugar Loaf on Guanabara Bay. It was between these two hills that the Portuguese captain Estácio de Sá and his squadron landed in 1565 and founded the city of São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro. Across the waters of Guanabara Bay, Cara de Cão faces Niterói, which had its origins in the settlement of São Lourenço, established in 1568. This is where Marcos Sacramento was born. Thus, Caracane represents not only the mythical incarnation of Rio de Janeiro but also the artist’s complex relationship with his city.

Caracane is another name for Cara de Cão, or Dog Face Hill, located just below Sugar Loaf on Guanabara Bay. It was between these two hills that the Portuguese captain Estácio de Sá and his squadron landed in 1565 and founded the city of São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro. Across the waters of Guanabara Bay, Cara de Cão faces Niterói, which had its origins in the settlement of São Lourenço, established in 1568. This is where Marcos Sacramento was born. Thus, Caracane represents not only the mythical incarnation of Rio de Janeiro but also the artist’s complex relationship with his city.

It follows that Caracane is a cycle of love songs for Rio de Janeiro; a chain of witty, poetic picture-postcards exploring various aspects of the metropolis—some charming, some decidedly less so but fascinating nonetheless.

Five of the nine Caracane songs were composed by Sacramento and Paulo Baiano, who’ve been a songwriting team since the early ’80s. Among these five we find the samba “Ares do Rio,” in which the poet Sacramento serenades his city as if she were a woman, her illuminated breasts the mountains of Sugar Loaf and Urca, fatefully located in that mythic spot of historic discovery. “Lilita,” incorporating samba-de-roda and maculelê patterns, celebrates the spontaneous music and dance people make in their backyards. “Pra Ver o Futebol” is a boisterous, whistle-punctuated hymn to soccer, in which Maracanã stadium is portrayed as a palace of so many kings. The samba/hip-hop “Rapa da Lapa” investigates the physical space of and some less tangible differences between two celebrated Rio squares, utilizing explicitly graphic terms rife with sexual, political, geographical, and literary puns. “Preta” is a tribute to Afro-Brazilian heritage and traditional samba.

Like beads in a necklace, these songs are interspersed with “Caricas II” and “Caricas III,” by Antonio Saraiva and Sergio Natureza. The first is a mordant exposé of some well-known Rio problems—litter, pollution, endangered wildlife—while the second paints a tongue-in-cheek picture of the myth that is Rio. This myth is further probed in “Caracane,” a waltz by Paulo Baiano and Sergio Natureza that serves as a grand summation of the themes of illusion and reality, past and present, beauty and tawdriness. Serving as glue to the Caracanerondo are two vignettes carved out from the song “Rio do Rio” by Fernando Morello, a funk tune turned leitmotiv.

Like beads in a necklace, these songs are interspersed with “Caricas II” and “Caricas III,” by Antonio Saraiva and Sergio Natureza. The first is a mordant exposé of some well-known Rio problems—litter, pollution, endangered wildlife—while the second paints a tongue-in-cheek picture of the myth that is Rio. This myth is further probed in “Caracane,” a waltz by Paulo Baiano and Sergio Natureza that serves as a grand summation of the themes of illusion and reality, past and present, beauty and tawdriness. Serving as glue to the Caracanerondo are two vignettes carved out from the song “Rio do Rio” by Fernando Morello, a funk tune turned leitmotiv.

Antonio Saraiva’s imaginative arrangements include all four shades of saxophone; trombones; flutes; piano; acoustic guitar and 7-string guitar; cavaquinho; contrabass; the full range of samba percussion instruments; whistles; clapping; backup voices; and in the song “Caracane,” a latter-day Greek chorus.

The Caracane style of melding progressive musical concepts with traditional Brazilian forms and acoustic arrangements has been dubbed Guanabeat by the poet/lyricist Sergio Natureza. The composer/journalist Mathilda Kóvak calls Caracane “The Sgt. Pepper of Samba” and even goes so far as to divide the history of popular Brazilian music—and especially of samba—into two periods: Before and After Caracane. The eminent music critic Tárik de Souza noted with approval the creative spirit embodied in this disc and a few others of its ilk—creativity that persists despite the Brazilian music industry’s current focus on marketing mediocre genres for mass consumption.

How the past illuminates the future

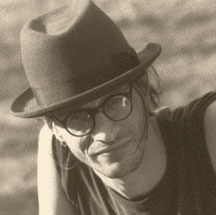

Caracane is the latest manifestation of a musical expression that began with Cão Sem Dono (Dog Without a Master, a reminder of how hard it is for the independent artist to deal with record companies). This was the name of Sacramento’s and Baiano’s first band, formed in the early ’80s. In 1984, Cão Sem Dono played Baiano’s compositions on the soundtrack of a medium-length film titled E a Propósito do Rio, directed by Roberto Moura. The band’s only album, Cão Sem Dono (1986), may best be described as experimental rock-cabaret, where the reference to samba is more implicit than obvious.

Caracane is the latest manifestation of a musical expression that began with Cão Sem Dono (Dog Without a Master, a reminder of how hard it is for the independent artist to deal with record companies). This was the name of Sacramento’s and Baiano’s first band, formed in the early ’80s. In 1984, Cão Sem Dono played Baiano’s compositions on the soundtrack of a medium-length film titled E a Propósito do Rio, directed by Roberto Moura. The band’s only album, Cão Sem Dono (1986), may best be described as experimental rock-cabaret, where the reference to samba is more implicit than obvious.

While singing his own early technopop, Sacramento also embarked on a parallel track for which he’s become better known: he emerged as a master interpreter of classic sambas—certainly the most outstanding of his generation and a natural heir to Orlando Silva, Mário Reis, and João Gilberto. His first recordings in this vein can be heard on the award-winning 1986 album Custódio Mesquita—Prazer em Conhecê-lo. Here he interprets two of the great stage composer’s 1940s standards in a style that has since become his hallmark: crystal-clear delivery that exposes the best in the music while avoiding any hint of mannerism or affectation.

While singing his own early technopop, Sacramento also embarked on a parallel track for which he’s become better known: he emerged as a master interpreter of classic sambas—certainly the most outstanding of his generation and a natural heir to Orlando Silva, Mário Reis, and João Gilberto. His first recordings in this vein can be heard on the award-winning 1986 album Custódio Mesquita—Prazer em Conhecê-lo. Here he interprets two of the great stage composer’s 1940s standards in a style that has since become his hallmark: crystal-clear delivery that exposes the best in the music while avoiding any hint of mannerism or affectation.

The Sacramento style came into full flower in his first solo CD, A Modernidade da Tradição (1994), in which the singer, with the innovative accompaniment of guitarist/arranger Mauricio Carrilho and crack percussionist Marcos Suzano, reveals hitherto unexplored facets of classic and lesser-known songs dating from several rich decades of Brazilian music.

A Modernidade da Tradição regales us with beautifully juxtaposed examples of prime malandro songs like “A Volta do Malandro” and “Largo da Lapa” (Lapa being one of Sacramento’s most frequently recurring themes). The malandro motif is blended with that of unrequited love in the masterpieces “Pela Décima Vez” and “Fez Bobagem.” Lost love is given further expression in “Mulher Sem Alma,” “Olhar Brasileiro,” “Infidelidade,” and “Lábios que Beijei,” the latter one of Orlando Silva’s greatest successes, here offered a fresh lease on life. Budding love is celebrated in “Morena,” while Brazil’s mixed heritage is honored in “Vela no Breu” and in “Canto das Três Raças,” where Sacramento proves that it’s possible to go beyond Clara Nunes’ famous interpretation. As always, there are references to samba and to singing, as in “Dos Prazeres das Canções,” “Genipapo Absoluto,” and “Apoteose do Samba” (see Sacramento’s solo CD discography for composer credits).

A Modernidade da Tradição regales us with beautifully juxtaposed examples of prime malandro songs like “A Volta do Malandro” and “Largo da Lapa” (Lapa being one of Sacramento’s most frequently recurring themes). The malandro motif is blended with that of unrequited love in the masterpieces “Pela Décima Vez” and “Fez Bobagem.” Lost love is given further expression in “Mulher Sem Alma,” “Olhar Brasileiro,” “Infidelidade,” and “Lábios que Beijei,” the latter one of Orlando Silva’s greatest successes, here offered a fresh lease on life. Budding love is celebrated in “Morena,” while Brazil’s mixed heritage is honored in “Vela no Breu” and in “Canto das Três Raças,” where Sacramento proves that it’s possible to go beyond Clara Nunes’ famous interpretation. As always, there are references to samba and to singing, as in “Dos Prazeres das Canções,” “Genipapo Absoluto,” and “Apoteose do Samba” (see Sacramento’s solo CD discography for composer credits).

A Modernidade da Tradição was released in Brazil on the SACI label, which ceased to be a going concern following the untimely death of its founder, the composer Maurício Tapajós. In 1997, a French edition came out on the Buda label. The fact that this landmark album is now available only on a French label is a sad commentary on the state of the Brazilian music industry.

Note: By 2004, the Buda release had gone out of print. The CD was reissued by Biscoito Fino in 2008.

In 1995 Sacramento added two classic soccer-related sambas to his repertorial treasure trove. They are to be found (if you can find the disc) on the superb SACI album Estácio & Flamengo—100 Anos de Samba e Amor.

In 1995 Sacramento added two classic soccer-related sambas to his repertorial treasure trove. They are to be found (if you can find the disc) on the superb SACI album Estácio & Flamengo—100 Anos de Samba e Amor.

A quick perusal of the Sacramento discography immediately reveals the absence of any artistic false steps—a claim not many recording artists can make. Everything Sacramento has done so far demonstrates astute judgement and impeccable musical taste. For his fans, this is reason enough to look forward to his future recordings with great anticipation.

These days, the singer is performing in a stage show celebrating the life and music of the great early samba composer Sinhô. We caught up with Sacramento (or Sacra, as his friends call him) between performances of É Sim, Sinhô and the launches of two CDs.

Daniella Thompson—Where did you grow up?

Sacramento—I was born in Niterói, the old capital of the State of Rio. Crossing by boat, it took twenty minutes to arrive at the then capital of the State of Guanabara: São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro. I am, therefore, a carioca (or carica) from Niterói.

DT—What are the special characteristics of Niterói? Do you still live there?

Sacramento—Niterói is only a small beach town. One of its principal characteristics is that from there you can see the most beautiful view of Rio de Janeiro. I was born and raised in Niterói, but I’ve been living in Rio de Janeiro for twenty years: Eu vim de barca, cantareira da ilusão… remember? [From the song “Ares do Rio” in Caracane; see lyrics.] Still, my passion continues for this town of mine, which today is practically another district of Rio. It’s a common pleasantry among us that you can find people from Niterói anywhere in the world. A friend of mine from Niterói who was living in London fell into a depression one typical rainy London evening and decided to go to the movies. He entered a small, almost deserted cinema; there were only about six people in the theater. Behind him sat a young couple. A scene in the film showed a bucolic garden, and as this garden appeared on the creen, the girl sitting behind my friend whispered to her boyfriend in Portuguese, “Look, this garden is just like Campo de São Bento!” [Campo de São Bento is a garden in Niterói.]

DT—What were your musical influences?

Sacramento—My mother and my aunts used to frequent the live shows of radio programs. In the 1940s and ’50s, there was no television in Brazil. Radio—and in particular the Rádio Nacional—was the great communication medium. And on the radio, the live shows were the stage for the great stars of popular music.

I was raised by women who sang the repertoire of the great female singers of Brazil: Linda Batista, Dalva de Oliveira, Inezita Barroso, Ademilde Fonseca, Isaurinha Garcia, Elizeth Cardoso, Marlene, and Emilinha Borba, among others. I learned to like this. I grew up hearing, in addition to all these women, the equally powerful voice of my father, who imitated the great male singers of the period: Orlando Silva, Francisco Alves, Moreira da Silva, Jorge Veiga, Cyro Monteiro, and Miltinho.

DT—Do you remember any particular songs that your parents sang?

Sacramento—I grew up hearing my mother sing, at the laundry sink and in the kitchen, a great success of one of Brazil’s best singers, Elizeth Cardoso. The song is “Canção de Amor,” by Chocolate and Elano de Paula. My father in turn took it upon himself to make sure that I learned the syncopated sambas of the great bambas: Geraldo Pereira, Jorge Veiga, Moreira da Silva, and many others. It’s difficult for me now to remember specifically one samba or another, for my old man’s repertoire was really varied.

DT—And later?

Sacramento—I was transformed into an adult (is it possible?), imitating both the women who raised me and my father. It couldn’t have been otherwise. I was, so to speak, predestined. I learned to sing. Through my adolescent friends I got to know the music of the world, different from what was performed in the live shows of the Rádio Nacional: the Beatles, Frank Zappa, the Rolling Stones, Ella Fitzgerald, Mel Tormé, Led Zeppelin, Chet Baker, Bola de Nieve, Mercedes Sosa, Sarah Vaughan, Miles Davis, and Henri Salvador, all of which led me to hear Brazilian music of another kind: Villa-Lobos, Egberto Gismonti, Hermeto Pascoal, Tom Jobim, Edu Lobo, Chico Buarque, and Elis Regina—the greatest of all the female singers.

Sacramento—I was transformed into an adult (is it possible?), imitating both the women who raised me and my father. It couldn’t have been otherwise. I was, so to speak, predestined. I learned to sing. Through my adolescent friends I got to know the music of the world, different from what was performed in the live shows of the Rádio Nacional: the Beatles, Frank Zappa, the Rolling Stones, Ella Fitzgerald, Mel Tormé, Led Zeppelin, Chet Baker, Bola de Nieve, Mercedes Sosa, Sarah Vaughan, Miles Davis, and Henri Salvador, all of which led me to hear Brazilian music of another kind: Villa-Lobos, Egberto Gismonti, Hermeto Pascoal, Tom Jobim, Edu Lobo, Chico Buarque, and Elis Regina—the greatest of all the female singers.

DT—Did you take singing lessons? Who taught you to sing?

Sacramento—When it comes to the study of singing, I had little class time during my life, but I always tried to get the most out of the little contact I had with ormal learning. In reality, my great teacher of singing (not to mention of music) was Elis Regina. I learned a lot hearing essa mulher [that woman; also the title of a song by Joyce and Ana Terra that Elis Regina recorded on her album of the same name].

DT—How old were you when you knew you wanted to be a professional singer?

Sacramento—When I was seventeen, I did some amateur theatre in Niterói and discovered that singing was what gave me the most pleasure. Since then I never lost contact with music. The rest, I think, you can imagine.

DT—The pleasure of singing, combined with diverse musical influences, yields what?

Sacramento—When you consider a salad, you think of something in which the right ingredients are well mixed. It can all become even more delicious, depending on the dressing. In the same way, the musical influences of my life are my parents singing, the radio playing, and the ’70s. I recognize that it’s fundamental to be always seeking the future in the past.

DT—You recorded your first album, Cão Sem Dono, in 1986.

Sacramento—Paulo Baiano has been my companion on this journey since the early ’80s. We met in the bars of Niterói and soon discovered our common passion for Elis. It was as a result of this encounter that I began to make music seriously—to compose, to sing, to sing, to sing… It was there that I also began to learn a mountain of things—about music and about life. With Paulo Baiano (plus Paulo Brandão on bass and Bernardo Quadros on drums), I founded Cão Sem Dono, a group that, almost fifteen years ago, defined itself as “tecnopop”—long before this definition became fashionable in the media (now with an H: technopop)—a sound that utilized the most up-to-date technology of that period (synthesizers, sequencers, and digital drums), at least here in Brazil. But we mixed our own music with all the influences I mentioned earlier: the whole tradition of Brazilian music.

DT—In 1986, the same year the album Cão Sem Dono came out, you also participated in the Acervo Funarte album Custódio Mesquita—Prazer em Conhecê-lo. These two albums couldn’t have been more different, and they set your dual style of simultaneously looking forward and backward.

Sacramento—The truth is that my musical universe has always been closer to Custódio Mesquita and his contemporaries, as you can perceive from my upbringing. It was Cão Sem Dono that was an incursion into experimentalism. My partnership with Paulo Baiano led me to become acquainted with other universes. I myself am surprised at this ability to move naturally through such different styles.

DT—Your recording of Custódio Mesquita’s “Promessa” is the best version I’ve ever heard. How did you end up with this gem?

Sacramento—Thank you for the praise. “Promessa” is just that, a pearl. I already knew this samba quite well. But I think that it’s only my contribution to an important disc in which I had the honor of being invited to participate.

DT—As long as we’re discussing your early recordings, I’d like to touch on your singing style. What strikes the listener (at least this listener) about your singing style is that it was both technically and emotionally mature and fully in control from the very beginning of your recording career. No struggle with the material was ever apparent. It’s as if you’d sprung fully formed as a complete professional. What did you do to prepare?

Sacramento—I don’t know. I just like to sing. I like to do this. I like it a lot—I sing every day. At times I have to force myself to think of other things.

DT—You played the role of Orlando Silva in the telenovela Kananga do Japão—a very fitting choice. In what year was it aired, and what were the circumstances? I assume this was a singing role. What did you sing?

Sacramento—Kananga do Japão [a dramatic TV series about the history of MPB; Kananga do Japão was a popular Rio dance and carnaval club founded in 1911, in whose hall many musical stars performed] was aired in 1989. The musical producer of the series called me and asked if I had a “vozeirão”; [“big voice”]. I said yes (imagine if I’d let this chance slip by!). I sang two very well-known songs from Orlando Silva’s repertoire. They were “Rosa” by Pixinguinha and “Carinhoso,” also by maestro Pixinguinha, with lyrics by Braguinha.

DT—I adore Orlando Silva’s 1937 recordings of these songs. It would be very interesting to hear your versions. Did you imitate Orlando’s style?

Sacramento—No, I didn’t imitate Orlando Silva, but I sang like a singer of the radio era.

DT—Your first solo disc was A Modernidade da Tradição—an instant classic.

Sacramento—This was a partnership with Mauricio Carrilho, already in the ’90s, where the immersion in the rich tradition of our music becomes even more radical than it had been in Cão Sem Dono.

DT—How did you come to make this disc? The choice of Mauricio Carrilho and Marcos Suzano as accompanists was absolutely perfect. Could you tell us something about the background to this production?

Sacramento—My encounter with Mauricio Carrilho was semi-casual. We were in his house and began to rehearse a repertoire for a series of shows in Rio de Janeiro. We became excited with the results, and it all ended up inside a studio in Lapa. We were joined by Marcos Suzano, and without rehearsals, in two weeks, the disc was ready. Mauricio adores working this way. It was an absolutely jazz-like experience. Everything live and spontaneous, as in jam sessions, only with samba. Maurício Tapajós heard it, liked it, and launched it on his label SACI. Teca Calazans also heard it, liked it, and released it on her label Buda Musique, in France. And thanks to all of that, we’re here now, having this conversation.

DT—Another classic disc in which you provided unforgettable interpretations is Estácio & Flamengo—100 Anos de Samba e Amor. Once again, as in the Custódio Mesquita album, you got to sing plums and turned them into definitive versions. How did you get those songs? Who made the decision?

Sacramento—Now you’re embarrassing me. But here’s the answer. It was another project of Maurício Tapajós to get all his ’cast together in a tribute to the escola de samba Estácio de Sá and to Brazil’s most famous soccer team, Flamengo, which celebrated its centennial in 1995. That year, Estácio chose Flamengo’s centennial as its carnaval theme. As one of the artists under contract to SACI, there I was in order to sing two sambas that I had selected from a long list presented to me by the producers. I’m glad you liked it. Here in Brazil the disc is absolutely unknown and rare.

DT—You’ve just released Caracane, which includes five songs you wrote with Paulo Baiano. How do the two of you collaborate? What comes first, the music or the lyrics?

Sacramento—I write the lyrics and send them to Paulo. He then sets them to music. In our case, I always write the lyrics first.

DT—So you are the one who determines the rhythm of a song?

Sacramento—Also.

DT—And the other songs on Caracane?

Sacramento—They were composed by Antonio Saraiva and Sergio Natureza, who, ironically, was recorded by Elis herself.

DT—With Clara Sandroni and the group Lira Carioca, you’ve recently recorded a CD and are performing in a show called É Sim, Sinhô. How did this project develop?

DT—With Clara Sandroni and the group Lira Carioca, you’ve recently recorded a CD and are performing in a show called É Sim, Sinhô. How did this project develop?

Sacramento—Sinhô is an admirable composer of the beginning of the 20th century. He’s called here the King of Samba. This project is the brainchild of Fernando Sandroni, Clara’s uncle. The work is still evolving, although we’ve been performing it for a while. In addition to singing the amusing sambas of Sinhô, I also tell the equally amusing stories that exist around this great composer.

DT—Clara Sandroni seems to be a constant presence in your career, at least since your first Cão Sem Dono album. You’ve sung backup on each other’s discs. What is the special musical affinity between you? Clara has published a book on singing. Do you and she share the same theories about this art?

Sacramento—Clara Sandroni is a great singer and my friend since the days of Cão Sem Dono, as you can already perceive. As for sharing theories, that’s inevitable, isn’t it? All that time together in dressing rooms, warming up the voice…

DT—From hearing your repertoire—songs like “Gol Anulado” (Canceled Goal), “E o Juiz Apitou” (And the Referee Whistled), and “Pra Ver o Futebol” (To Watch Football)—one can’t help but draw the conclusion that you’re a serious football fan.

Sacramento—Yes, I adore football. I root for BOTAFOGO!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

DT—And I was convinced you were a Flamengo fan…

Sacramento—Please!!!!!!!

DT—Any other predilections?

Sacramento—What I really like is carnaval. Ah! I’m a SALGUEIRENSE!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

DT—Do you parade with Salgueiro in the Sambódromo?

Sacramento—No. I don’t like the Sambódromo. It’s an ugly and anti-musical structure. Samba has been seriously damaged since the carnaval parades shed their improvised character. When the grandstands were constructed each year [in the street], there used to be anarchy more appropriate to the nature of carnaval.

DT—What’s the next station on your journey?

Sacramento—Continuing to frequent the botequins of Rio de Janeiro, Paris, London, Bogota, Baghdad, Buenos Aires, Canada, Austria, Cuba, and all, absolutely all of Africa, is certainly in my plans…

A disc is born

Antonio Saraiva on the Caracane production

Daniella Thompson—How did you meet Sacramento?

Saraiva—Sacra and I have friends in common: Rita Peixoto, Fernando Morello, Paulo Baiano, Paulo Brandão (of Aquarela Carioca); but we weren’t close. The first time we worked together was in a performance presented at Espaço Cultural Sérgio Porto (a place where many of us had the chance—and the freedom—to show our work). I did a song about Curitiba, a kind of bloco afoxé [Afro-Bahian carnaval parade group] called “Filhos de Gdanski,” a play on Filhos de Gandhi and Gdansk, Poland. We were all dressed in suits and ties, like business executives—very white, not Afro-Brazilian at all. It was like a Wall Street afoxé, a joke about purism. I believe that in Brazil there’s no room for either Sacred White or Sacred Black.

Sacramento asked to sit in (there’s a funny backstage photo of this happening). This was in 1994. The same year, I was invited to give a course in ‘free composition’ (whatever that might be) in Curitiba, where I met the poet/lyricist Sergio Natureza. He was at the same workshop, teaching ‘lyrics classes.’ We became close and decided to do something together. Sergio was one more common friend I had with Sacramento. In 1996 I was invited to play at the opening of a poetry magazine called O Carioca, edited by the poet Chacal (many musicians also write in this magazine), and I invited Sacramento to sing the songs I had set to Sergio’s award-winning poems about Rio. This was the premiere of the “Caricas” suite. I played the piano and Sacramento sang “Caricas” I, II and III. We recorded “Caricas I” in 1996 on the CD Ovo—Novíssimos and “Caricas” II and III on Caracane.

Sacramento asked to sit in (there’s a funny backstage photo of this happening). This was in 1994. The same year, I was invited to give a course in ‘free composition’ (whatever that might be) in Curitiba, where I met the poet/lyricist Sergio Natureza. He was at the same workshop, teaching ‘lyrics classes.’ We became close and decided to do something together. Sergio was one more common friend I had with Sacramento. In 1996 I was invited to play at the opening of a poetry magazine called O Carioca, edited by the poet Chacal (many musicians also write in this magazine), and I invited Sacramento to sing the songs I had set to Sergio’s award-winning poems about Rio. This was the premiere of the “Caricas” suite. I played the piano and Sacramento sang “Caricas” I, II and III. We recorded “Caricas I” in 1996 on the CD Ovo—Novíssimos and “Caricas” II and III on Caracane.

DT—How did you get involved in the production of Caracane?

Saraiva—The production nucleus of Sacramento’s previous solo disc, A Modernidade da Tradição, consisted of Segio Natureza, Fernando Morello, and Mauricio Carrilho. When Sacramento decided to make a new album, it was his intention to continue along the same road as A Modernidade but maybe in a new vehicle (or at a different speed). He asked me to work on this project because, as he told me, he was thinking that I could give it ‘something else’ that he was looking for. Sacramento gave me a tape with many songs that he was thinking of recording; some already had arrangements by Paulo Baiano.

I can’t remember now, but I think that only one or two of these songs didn’t make it into Caracane. Marcos decided to record “Caricas” II and III as well. My job was to create a continuity between A Modernidade and this new record, to make this one a different record, and to create a unity within it. The original idea was to form another team to produce this album, but Fernando Morello was very busy, and Sergio Natureza also couldn’t commit himself to working continuously on this project. So I ended up doing the artistic and musical direction of this album.

DT—And you also put your stamp on the material.

Saraiva—One of the songs that didn’t make it into Caracane was an old song from the radio era. I proposed to Sacra that he do an authorial album of previously unrecorded material. In addition to being a good singer, he’s also a great songwriter. In doing the arrangements, my task was to find a way backward in order to go forward. Paulo Baiano’s songs and harmonies have a natural sophistication and complexity. He is an MPB/jazz/progressive rock-influenced piano player, and his songs have a definite diomatic accent.

I did it my way. I tried to put these songs in more of a ‘roots’ context. I wrote down the percussion, guitar, and horn parts to produce this rootsy feel. All the parts were fully written—even the percussion parts. Usually percussion parts are not written; musicians play a vamp or a groove. I treat percussion as I would any other instrument in the orchestration. I like to create my own patterns. This is also the case with the 7-string phrases that traditionally are improvised. The idea is to make the arrangements part of the song. It’s a pop-music concept. I love the contrast between rawness and sophistication (Ellington and Mingus showed me the way).

DT—How did the songs change as a result of your arrangements?

Saraiva—Baiano’s style is more stylized (bossa/jazz/funk-flavored). I tried to reveal the basic aspects of his harmonies and sometimes I completely changed the mood or the rhythm of a song. “Rapa da Lapa” used to be a kind of hip-hop with jazzy parts. “Preta” was a samba-funk. “Lilita” also was very different originally. “Caracane” was exactly as it appears on the CD but did not have the candomblé rhythm with the chorus. Fernando Morello’s “Rio do Rio” was originally a melodic funky tune with many parts and more lyrics. I cut many parts of his song and made it almost a refrain. Fernando says that it’s better now than when he composed it—this song got shorter but you can hear it many more times [laughs].

Saraiva—Baiano’s style is more stylized (bossa/jazz/funk-flavored). I tried to reveal the basic aspects of his harmonies and sometimes I completely changed the mood or the rhythm of a song. “Rapa da Lapa” used to be a kind of hip-hop with jazzy parts. “Preta” was a samba-funk. “Lilita” also was very different originally. “Caracane” was exactly as it appears on the CD but did not have the candomblé rhythm with the chorus. Fernando Morello’s “Rio do Rio” was originally a melodic funky tune with many parts and more lyrics. I cut many parts of his song and made it almost a refrain. Fernando says that it’s better now than when he composed it—this song got shorter but you can hear it many more times [laughs].

What I did was to listen to the tapes that Sacramento gave me with the songs he wanted to sing in the record, write down the harmonies and melodies, and, from the music and lyrics on paper, begin to think how to treat each song to (re)create a coherent unity. The idea was to have a link with A Modernidade da Tradição and take it a step forward.

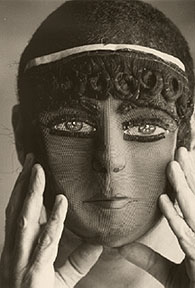

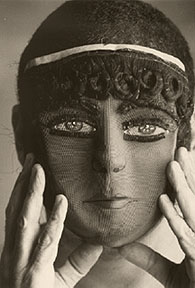

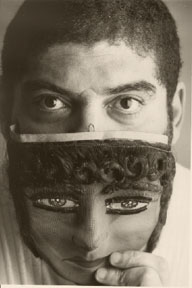

DT—I wanted to ask you about the ‘Greek chorus’ you have in the song “Caracane.” To my mind it ties in perfectly with that mask that Marcos wears in the cover photo. Do you see any connection?

Saraiva—I liked very much this ‘Greek chorus’ remark. You create a beautiful connection. Marcos says that this mask tells about velhos carnavais (old carnavals). Carnaval is connected to the Romans. Romans are connected to Greeks, so…

DT—Caracane took almost two years to finish. How did the recording sessions go?

Saraiva—We recorded Caracane in a small studio at a music school. As all the arrangements for all the parts were pre-written, we recorded in many weird ways. It was impossible to have the whole band (or even the rhythm section) in the studio at the same time, so we made a lot of overdubs to get the percussion parts (and the desired weight) recorded. Sometimes this was the last thing we did on certain tracks. I remember Bruno Migliari, the bass player, alone in the studio (where there was room only for himself and his acoustic bass) playing his written bass lines with just the metronome and no other parts—nonsense music. Sacramento looked at me, and I could hear his thinking: “What the hell is this?!”

But we had a lot of fun doing this album. A lot! The recording sessions went through the night, and we (me and Sacra) always looked for a beer after the job, when people were having café da manhã [breakfast] at the botequins, and we had talking parties at 8 am and going home saying goodnight to everybody at eleven in the morning.

DT—The instrumentals were recorded in 1996 and the voice in 1997. What occurred to make this necessary?

Saraiva—After we finished the recordings we tried a mix that didn’t satisfy us, because the guy who worked on it treated this as an ordinary samba recording. Sacramento was also not satisfied with the voice sound and re-recorded it in another studio (one of the best in Rio) under Fernando Morello’s supervision. At this time I was busy working on ballet music for the choreographer Paula Nestorov [Chegançaa; RioArte Digital], so I was not in these sessions.

The good thing was that Fernando was available again to join the team, so he did the mixing. Fernando is an excellent musician with technological know-how; the perfect person for this job. He knows about music and doesn’t discriminate between different styles. It was very good to work with him to recreate from all those tracks the atmosphere (that in act never existed, because the musicians hadn’t played together) that we wanted for Caracane. The mixing sessions turned into a great discussion about aesthetics, technology, life, love, Villa-Lobos, electronic music, rock, Debussy, and many other topics.

DT—The mastering didn’t happen until 1998, and it was done in Paris, of all places. What an odyssey for this album.

Saraiva—After zillions of versions, Caracane was ready. But Sacra was out of money and had to wait to master it (time is money). Meanwhile, he tried to sell the record to some labels. Much talk but no action. In February 1998 I got a call from Sacramento, telling me he was going to do some concerts in France during the carnaval, but he had a problem: the guitar player of the band he had organized for these shows had left. I said that I knew somebody who could do the job, but Sacra asked me to play the guitar and take charge of the musical direction. Okay! Here we go! The event was a surrealistic carnaval at a ski resort near Switzerland called Meribel and Aix-les-Bains, with samba schools, parades, capoeira, etc.

Sacramento was asked to do a bossa nova-oriented repertoire, and he chose songs by Caymmi, Edu Lobo, and Tom Jobim. The band was fine: Délia Fischer (piano), Renato Massa (drums), Marcos Cunha (bass), and myself on sax and guitar. After the concerts, Sacra’s plan was to go to Paris and master the record there and also to make contact with Teca Calazans from Buda Musique, the label that had released A Modernidade da Tradição in Europe. The mastering was fine and easy and cheap (Fernando did a very good job; his final mix was almost a mastering). We spent a week in Paris (the mastering was a single afternoon’s session) talking, drinking, and tasting the city with some old and new friends.

Back in Brazil, the third man reappeared: Sergio Natureza got the connection with Dabliú, and they released the record.

Acknowledgements: My thanks go to Dil Fonseca and Edith Lacerda for their invaluable and unstinting editorial contributions. This article is dedicated to my dear friend Guido Assao, without whose help, support, and eagle eye I couldn’t have hoped to complete my Marcos Sacramento collection.

From Cão Sem Dono to Cara de Cão

The Marcos Sacramento Discography

Cão Sem Dono (LP; 1986)

Boas Produções e Gravações Ltda. LPB-002; 992378-1

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Paulo Baiano (keyboards)

Paulo Roberto Brandão (bass)

Bernardo Quadros (drums)

Guests: Clara Sandroni, Laura de Vison, Patrícia Vergara, Julinho Moretzsohn, Luiz Cláudio, Denise Grimming, and Paulo César Soares.

Side A

01. Sinal Fechado (Paulinho da Viola)

02. Eu Não Sabia Nada (Paulo Baiano/Roberto Moura)

03. Tango (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

Side B

01. Luz del Fuego (Cláudio Lourenço/Paulo Baiano)

02. Nu Cinema (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

03. Todas as Noites (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

Custódio Mesquita—Prazer em Conhecê-lo (CD; 1986)

Acervo Funarte/Atração Fonográfica ATR 32040

An award-winning collection of songs written between 1932 and 1946 by the important stage composer Custódio Mesquita. Also with Marlene, Ney Matogrosso, Rosana Toledo, Amélia Rabello, and conjunto Coisas Nossas.

Tracks:

Promessa (Custódio Mesquita/Evaldo Ruy; 1943)—samba

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Cristóvão Bastos (piano & arrangement)

Jorjão (contrabass)

Rafael Rabello (7-string guitar)

Picolé (drums)

Clodoaldo (percussion)

Valsa do Meu Subúrbio (Custódio Mesquita/Evaldo Ruy; 1944)—waltz

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Cristóvão Bastos (piano & arrangement)

Jorjão (contrabass)

Rafael Rabello (7-string guitar)

Lura (cello)

A Modernidade da Tradição (CD; 1994)

SACI 8030 (Brazil)/Buda Musique 82920-2 (France)

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Maurício Carrilho (guitar)

Marcos Suzano (percussion)

Musical direction & arrangements: Maurício Carrilho

Tracks:

01. A Volta do Malandro (Chico Buarque)

Largo da Lapa (Wilson Batista/Marino Pinto)

02. Pela Décima Vez (Noel Rosa)

Fez Bobagem (Assis Valente)

03. Mulher Sem Alma (Nélson Cavaquinho/Guilherme de Brito)

04. Morena (Maurício Carrilho/Paulo César Pinheiro)

05. Olhar Brasileiro (Eduardo Dusek/Luís Carlos Góes)

06. Canto das Três Raças (Mauro Duarte/Paulo César Pinheiro)

07. Lábios Que Beijei (J. Cascata/Leonel Azevedo)

08. Vela no Breu (Paulinho da Viola/Sérgio Natureza)

09. Dos Prazeres das Canções (Pericles Cavalcante)

Genipapo Absoluto (Caetano Veloso)

10. Infidelidade (Ataulfo Alves)

11. Apoteose do Samba (Mano Décio da Viola/Silas de Oliveira)

Estácio & Flamengo—100 Anos de Samba e Amor (CD; 1995)

SACI 8060/S

A collection of classic sambas connected with the escola de samba Estácio de Sá and the Rio soccer club Flamengo, recorded on the occasion of Flamengo’s centennial, which Estácio used as its theme in the 1995 Carnaval. Also with Alza Alves, Amélia Rabello, Beth Carvalho, Cristina [Buarque], Chico Buarque, Carlinhos Vergueiro, Dona Ivone Lara, João Nogueira, Paulo Malaguti, Paulo César Pinheiro, Walter Alfaiate, Wilson Moreira, and Zé Keti. Special participations by Elton Medeiros, Luciana Rabello, Miúcha, MPB-4, Maurício Tapajós, Pií, Sérgio Santos, and Simone Cruz.

Arrangements & production: Maurício Carrilho & Maurício Tapajós

Tracks:

Gol Anulado (João Bosco/Aldir Blanc)

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Maurício Carrilho (guitar)

Luis Otávio Braga (7-string guitar)

Luciana Rabello (cavaquinho)

Oscar Pelon (pandeiro)

Beto Cazes (surdo & reco-reco)

Marcos Suzano (matchbox & tan-tan)

Alza (shout)

E o Juiz Apitou (Wilson Batista/Antônio Almeida)

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Maurício Carrilho (guitar)

Luis Otávio Braga (7-string guitar)

Luciana Rabello (cavaquinho)

Pedro Amorim (bandolim)

Beto Cazes (repique w/ vassoura)

Marcos Suzano (pandeiro grave)

Tribute to the Old Sambistas of Estácio:

Mandei Pintar (public domain/Hermínio Bello de Carvalho)

Singers: Amélia Rabello, Marcos Sacramento, Elton Medeiros, Miúcha, Carlinhos Vergueiro & SACI Chorus

Nem É Bom Falar (Ismael Silva)

Singers: Chico Buarque & Marcos Sacramento

Ovo—Novíssimos (CD; 1996)

RioArte Digital RD/01696

An anthology of contemporary composers, featuring the work of Suely Mesquita & Rodrigo Campello; Bia & Mário Grabois; Pedro Luís; Ivan Zigg; Arícia Mess; Rodrigo Cabelo; Luís Capucho; Mathilda Kóvak; Tuins; Fred Martins & Marcelo Diniz; and Antonio Saraiva & Sérgio Natureza.

Track:

Caricas I (Antonio Saraiva/Sérgio Natureza)

Marcos Sacramento & Antonio Saraiva (voice)

Antonio Saraiva (keyboards, tenor & soprano saxophones)

Arrangement: Antonio Saraiva

Caracane (CD; 1998)

Dabliú DB 0052; distributed by Eldorado

Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Antonio Saraiva (piano, cavaquinho, saxophones, percussion, whistle, clapping, voice)

Bruno Migliari (acoustic bass)

Paulo Baiano (piano in “Caracane”)

Rodrigo Campello (7-string guitar, cavaquinho)

Zé Al (tenor sax, flutes)

Quito Pedrosa (alto sax)

Henrique Band (baritone sax)

Aramis Guimarães (trombones)

Celso Alvim (percussion)

Sidon Silva (percussion)

Chorus in “Caracane”: Antonio Saraiva, Carlos Uzeda, Marcos Sacramento, Paulo Baiano, Pedro Luis, Sérgio Natureza, Sidon Silva & Valfredo Guida.

Arrangements: Antônio Saraiva

Tracks:

01. Caricas III (Antonio Saraiva/Sérgio Natureza)

02. Lilita (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

03. Rio do Rio—vignette (Fernando Morello)

04. Ares do Rio (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

05. Caricas II (Antonio Saraiva/Sérgio Natureza)

06. Rapa da Lapa (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

07. Pra Ver o Futebol (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

08. Rio do Rio—vignette (Fernando Morello)

Preta (Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

09. Caracane (Paulo Baiano/Sérgio Natureza)

É Sim, Sinhô (CD; 1999)

Lira Carioca CS 444

A tribute to José Barbosa da Silva—”Sinhô”—the most famous Carioca composer of the 1920s. Considered the first great samba stylist, Sinhô is known as O Rei do Samba (the King of Samba).

Clara Sandroni & Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Lira Carioca:

Fernando Sandroni (piano)

Jurandir Meireles (contrabass)

Clarinha Teixeira (cavaquinho)

Sérgio Magalhães (soprano sax & flute)

Adílson Roque (percussion)

Arrangements & musical direction: Fernando Sandroni

All songs by Sinhô unless otherwise noted.

Tracks:

01. A Favela Vai Abaixo

02. Fala Meu Louro

03. Mal de Amor

04. Sabiá

05. Gosto Que Me Enrosco

06. Burucuntum

07. Macumba Gegê

08. Amar a Uma Só Mulher

09. Coplas da Nota de Dez (A. Pimentel/M. Sampaio)

10. O Mugunzá (Francisco Carvalho/Bernardo Lisboa)—a 19th-century lundu

11. Adeus (Noel Rosa/Ismael Silva)

12. Burro de Carga/Carga de Burro

13. Jura

14. Não Quero Saber Mais Dela

15. O Pé de Anjo

Marubá (CD; pre-release)

The debut album of composer/singer Dil Fonseca, featuring two songs lettered by Marcos Sacramento—one with his participation.

Track:

Boreste (Dil Fonseca/Marcos Sacramento)

Dil Fonseca & Marcos Sacramento (voice)

Dil Fonseca (guitar, percussive effects)

Dôdo Ferreira (electric bass)

Carlos Fuchs (voice & triangle)

The complete updated and illustrated Marcos Sacramento discography may be found on the website Musica Brasiliensis.

Serenading the City

Songs from Caracane

Caricas III (Antônio Saraiva/Sérgio Natureza)

Restinga da Marambaia

Urubus na Sapucaia

Um morcego de Atalaia

Jandaia desarvorou

É permitida a gandaia

Cada um com a sua laia

A manhã fugiu da raia

Porque a tarde não tardou

O michê de mini-saia

despachado em plena praia

Quando o sol Césardesmaia7

no pontal do Arpoador

Vem a noite de tocaia

O céu cor de bala toffee9

O bofe comendo um misto dentro

da sauna a vapor

E lá do alto, benquisto

Brilha o Cristo Redentor

Perdoando os prejuízos causados

pelo calor.

Ah! Rio, quem te inventou?

Caricas1 III (Translation: Edith Lacerda)

Restinga da Marambaia2

Black vultures in the Sapucaia3

A bat of Atalaia4

Jandaia5 disoriented

Binging is allowed

Each one with its own kind

The morning ran away

Because the afternoon did not delay

The michê6 in a mini-skirt

dispatched on the open beach

When the sun faints7

in the point of Arpoador8

Comes the night in ambush

The toffee-colored sky9

The guy eating a sandwich

in the steam sauna

And there, from above, well-loved

Shines Christ the Redeemer

Forgiving the damages inflicted

by the heat.

Ah! Rio, who invented you?

Notes:

1 Caricas: contracted form of Cariocas (people born in Rio)

2 Restinga da Marambaia: coastal area outside Rio

3 Sapucaia: former island in Guanabara Bay that was land-filled to accommodate the campus of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

4 Atalaia: coastal area near Rio

5Jandaia: a kind of parakeet

6 Michê: female, male, or transvestite prostitute

7 Césardesmaia: a pun on desmaiar (to faint) and Rio’s former Mayor César Maia

8 Pontal do Arpoador: a point of sand at Ipanema beach

9 Bala Toffee: name of a candy

Ares do Rio(Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

Teus seios,

os vi numa festa entre copos

e luzes,

pessoas, olhares, sorrisos,

são seios,

são seios pontudos, os bicos acesos,

ares de Pão de Açúcar, de Cara de Cão:

São Salvador, São Sebastião.

Glória, Glória, Glória.

Os brilhos,

eu via de longe, e até hoje me lambem

teus mares batendo, batendo,

São brilhos,

filhos das águas que entram na barra

lavam o Pão de Açúcar e o Cara de Cão

São Salvador, São Sebastião.

Glória, Glória, Glória.

Eu vim de barca, cantareira da ilusão,

P’ressa chapada te amar,

timbrar meu coração

timbrar meu coração

e a claridade que faz

desta cidade meu chão

é meu mais puro devaneio,

meu samba pauleiro

é o meu Rio de Janeiro (bis)

é o meu Rio…

Airs of Rio(Translation: Edith Lacerda)

Your breasts,

I saw them at a party among glasses

and lights,

people, glances, smiles,

they’re breasts,

they’re pointed breasts, their nipples lit,

airs of Sugar Loaf, of Cara de Cão1:

São Salvador2, São Sebastião.3

Glória, Glória, Glória.4

The glitters,

I used to see them from afar, and still today

your seas lap me while beating, beating,

They’re glitters,

sons of the waters that enter the sandbar

washing Sugar Loaf and Cara de Cão

São Salvador, São Sebastião.

Glória, Glória, Glória.

I came by boat, the ferry of illusion5

To this plain to love you,

to stamp my heart

to stamp my heart

and the brightness that makes

this city my ground

is my purest daydream,

my heavy samba

it’s my Rio de Janeiro (bis)

it’s my Rio…

Notes:

1 Cara de Cão: Dog Face Hill at the foot of Sugar Loaf; site of the founding of Rio de Janeiro in 1565

2 São Salvador: a square in Rio

3 São Sebastião: patron saint of Rio; the city’s historic name is São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro

4 Glória: a district of Rio

5 Barca cantareira: the ferryboat that crosses Guanabara Bay from Niterói to Rio

Rapa da Lapa

(Paulo Baiano/Marcos Sacramento)

O que separa a Lapa da Cinelândia

são algumas calcinhas pretas

e cor-de-rosa

sacanagem,

é o que separa uma

praça da outra ou…

Alguns traçados, ou umas pretas,

um tufo de rosas,

falsas rosas, lapas de pretas,

sacanagem,

as pretas e as rosas, verdade, mentira.

O que separa a Cinelândia da Lapa

são uivos de prazer,

o Morro dos Prazeres, seres eternos,

Largos, Machados, sacanagem,

vulvas e pirocas, pipocas e viúvas,

Automóvel Club.

Homens de verdade,

falsas mulheres no Passeio Público,

sacanagem!!!

Cecílias, Meireles, estreitos Gonçalves,

aladas marrecas, sacanagem

Cálices de pomba-gira, fálices

de cala a boca,

tapa na cara, sacanagem

o que separa uma praça da outra é…

…Sacanagem.

Rapa1 of Lapa(translation: Edith Lacerda)

What separates Lapa2 from Cinelândia3

are some black and

pink panties

debauchery,

It’s what separates one

square from the other or…

Some drinks, or some black shes,4

a bunch of roses,

false roses, lapas5 of black shes,

debauchery,

the black ones and the pink ones, truth, lie.

What separates Cinelândia from Lapa

are howls of pleasure,

the Mount of Pleasures,6 eternal beings,

Largos, Machados,7 debauchery,

vulvas and pricks, popcorn and widows,

Automobile Club.8

True men,

false women in the Passeio Público,9

debauchery!!!

Cecílias, Meireles,10 narrow Gonçalves,11

winged marrecas,12 debauchery

Chalices of pomba-gira,13 fálices14

of shut up,

a slap in the face, debauchery

what separates one square from the other isÖ

ÖDebauchery.

Notes:

1 Rapa: police; a pun on RAP (Rhythm and Poetry)

2 Lapa: famous old bohemian quarter in Rio, now a well-known prostitution zone

3 Cinelândia: a square in central Rio; old cultural center full of cinemas; in the ’60s it was an important stage for political demonstrations

4 Pretas: black women or transvestites

5 Lapas: large chunks

6 Morro dos Prazeres: a slum hill in Santa Teresa, a district adjoining Lapa

7 Largos/Machados: Largo do Machado, a square in Catete, a district near Lapa

8 Automóvel Club: a building in Lapa

9 Passeio Público: a square between Lapa and Cinelândia

10 Cecílias/Meireles: Cecília Meireles, a theater in Lapa named after the Brazilian poetess

11 Gonçalves: a street named after Gonçalves Dias, a Brazilian poet

12 Marrecas: a street in Rio; teal ducks

13 Pomba-Gira: a feminine entity of Umbanda

14 Fálices: a pun on falar (to speak) and cale-se (shut up!)

The writer publishes the online magazine of Brazilian music and culture

Daniella Thompson on Brazil and the website Musica Brasiliensis, where she can be contacted.