Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration is embarking on a project of cultural and historical revision. In September, the Cinemateca Brasileira, Brazil’s library of national films, was “occupied” by military and extreme-right politicians who criticized the institution’s “cultural Marxism” and promised a future film festival devoted to rehabilitating the image of the country’s military dictatorship.

Also in September, Ancine, Brazil’s national film development agency, saw its funding suddenly cut by nearly one half. Former Minister of Culture Marcelo Calero pointed out that all countries must invest in creative as well as scientific development, and that “these are measures that have a very strong ideological component.”

The Brazilian Association of Documentary and Short Filmmakers (ABD) issued a statement in which they declared that in view of the occupation of the Cinemateca and the Ancine cuts, the country’s film community was being “violated materially and symbolically by far-right activists.”

This week, the government announced the creation of a new video series under the aegis of TV Escola (TV School) entitled “Brazil: The Last Crusade” in which “the hidden history of Brazil will be revealed.” Production company Brasil Paralelo (Parallel Brazil) vows to “combat leftist ideas” with the series, whose first episodes can be seen for free on Youtube. Future segments will be available on a pay-per-view basis.

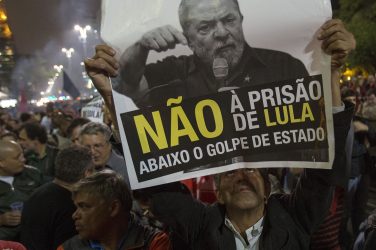

The first video opens with what producers imply is the false narrative of Brazil, with images of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, long lines and crime. Then drone shots of monuments, churches, and skyscrapers are juxtaposed with stacks of books and talking heads. Conspiracy theorist Olavo de Carvalho, who contests that the earth is round and claims Pepsi is sweetened by aborted fetuses, is prominently featured.

This week, Carvalho demeaned both the former president and another Brazilian humanitarian of humble origins when he commented on the author of “Pedagogy of the Oppressed”: “What did Paulo Freire ever do for Brazil? Not a damn thing. He didn’t even teach Lula how to read.”

One of the missions of the Cinemateca is the preservation and continued distribution of the works of one of the most remarkable periods in the history of filmmaking, the Cinema Novo, a movement that began in the mid 1950s.

Influenced by Italian neo realism, “God and the Devil in the Land of the Sun” presented in the US as “Black God, White Devil” (Gláuber Rocha, 1964) starkly depicts the desperate and violent history of the inland northeast, the desert region known as the sertão. Afro-Brazilian mystics and mestiço bandits, known as “cangaceiros”, battle ruthless landowners to survive the extreme drought.

Rocha was forced into exile by the military dictatorship for ten years, only returning when he was transferred from a Portuguese hospital with a lung infection, dying days later at 42.

“How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman” (1971), by Nelson Pereira dos Santos, was filmed almost entirely in the Tupi language and satirizes the literal cannibalism of the Tupinamba people and the imperialist cannibalism committed by Europeans in the Americas. The Tupinamba may have eaten the Frenchman but they were later decimated by colonialism.

In “Bye, Bye Brasil” (1979, Carlos Diegues), a carnival caravan struggles to find an audience in a seemingly deserted town, finally happening upon a crowd gathered around a television set.

As the traveling show continues to move in search of better prospects, they witness the death and destruction of the wilderness at the hands of industrialists. After meeting a group of indigenous people driven from their ancestral lands, the women of the circus are forced into prostitution in order to earn money.

Ultimately the indigenous people are delighted to get their first airplane ride as they are recruited as laborers, and the circus leaders buy a splashy caravan covered in neon lights with their new money, declaring that they are changing course and going to bring modernity to what’s left of the jungle.

“Pixote” (1981, Héctor Babenco) and “City of God” (2002, Fernando Meirelles, Kátia Lund) are brutal explorations of the lives of street children forced to adapt to the endemic violence of the enormous shantytowns that cling to the hills above or reside on the peripheries of São Paulo, Rio and Brazil’s other major cities.

Both films used non-professional actors, as Gláuber Rocha did in the 1960s, drawn from the cities where homeless children are “cleansed” or killed by the police. The documentary “City of God – 10 Years Later” revisits the protagonists of that film and finds that many were unable to escape the problems.

“Central Station” (1998, Walter Salles) follows a retired teacher and an orphaned boy living in the railway station on an odyssey across the vast expanse of Brazil by bus and truck. The teacher first sells the boy to an organ trader in order to buy a television, but then remorsefully decides to steal him back and take him from Rio de Janeiro to Bahia on a search for his family.

Fernanda Montenegro, now 90, who played the retiree, was pictured on the September cover of Brazilian magazine “Quatro Cinco Um” covered in heavy rope atop a stack of books, in an obvious reference to witch and book burning. She was called “sordid” and “liar” by failing conservative Christian director Roberto Alvim, who in November was named Minister of Culture by Bolsonaro.

While Brazil’s commercial telenovelas (soap operas) almost exclusively focus on wealth and riches, mostly populated with actors of European descent, the films supported by Ancine and the Cinemateca explore the plurality and reality of Brazil employing uniquely Brazilian innovations.

Brazil had a long history of censorship during the military dictatorship of 1964 to 1985, and the U.S. had an overt period of censorship of the arts a few years earlier. Brazilian multi-media artist Vik Muniz, who lives and works between New York and Rio, warns that Bolsonaro, or Trump in the U.S., are not the only ones to blame. “You have to understand that we elected these people,” he points out. “Whether you like it or not, [they] represent the bulk of the people.”

But that bulk of people are not homogeneous, nor are they inhabiting the neighborhoods glorified in “The Last Crusade”. The new United Nations Human Development Index (HDI), which came out this month of December, places Brazil in second place among the most unequal countries in the world, with more than 28% of the nation’s wealth concentrated in the hands of a mere 1% of the population.

By focusing on describing only the richest in Brazil, Bolsonaro is ignoring the vast majority of the country, and the richness of their diverse stories.

Danica Jorden is a writer and translator of French, Spanish, Portuguese and Italian.

This article appeared originally in Common Dreams – https://www.commondreams.org/