The storming of the three main symbols of the Brazilian republic – the supreme court, the national congress and the presidential palace – is the kind of event that could shape the country’s history. While Brazil has gone through military coups and social turmoil since it became independent in 1822, never before have Brazilians witnessed such widespread disregard for political institutions.

This is a story that starts around 2018, when Jair Bolsonaro – then a lackluster congressman known for supporting the military dictatorship and publicly praising notorious torturers – launched his presidential candidacy. In the name of God, the fatherland and traditional family values, the retired army captain vowed to “drain the swamp” of politics and usher in a new era for Brazil.

In his vision, state policies would no longer be necessary. Political authority would naturally stem from business people, religious leaders, armed militiamen and – above all – the president’s messianic figure.

This combination of authoritarian populism and social Darwinism is not new. It lies at the foundations of far-right movements that have gained momentum worldwide in recent years. And it sheds light on the Bolsonarist phenomenon, helping us make sense of Brazil’s “black Sunday”.

Bolsonarism is a profoundly anti-democratic movement that conflates elements of the US far-right – most notably Trumpism – and Brazil’s long history of social inequality and militarism into a whole new digital language. WhatsApp and social media have been key to attracting supporters that have become increasingly suspicious of the political system over the previous decade.

This popular disillusionment among certain groups has been mostly due to corruption scandals, growing urban violence and to policies under the then – and now again – president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, that favored Brazil’s poorest.

In his path to the presidency, Bolsonaro was able to tap into people’s emotions. He brought millions of Brazilians together by mobilizing elements of hatred, fear and resentment, and offered them something to fight against – namely, communism.

Undermining democracy

For the start of his tenure, Bolsonaro moved decisively to undermine Brazil’s democratic institutions and state capacity on the grounds that he was saving the country from communism. By pitting his supporters against imaginary enemies he could successfully dodge accusations of incompetence, corruption – and even crimes against public health during the COVID pandemic which killed nearly 700,000 Brazilians.

The Bolsonaro administration’s survival might be down to the loyal support of a coalition of business people, the farming lobby, evangelical leaders and members of the armed and security forces. A key element of his governing strategy was to attack whoever spoke against the interests of these groups: the supreme court, congress and the mainstream media among his favorite targets.

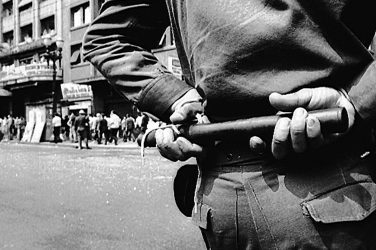

There have been allegations that on September 7 2021, Brazil’s independence day, Bolsonaro planned to summon supporters to cause turmoil in the streets across the nation. The idea was supposedly to justify a military takeover through a state of emergency. However, the higher ranks of the armed forces did not provide clear support.

This does not mean that the military are innocent when it comes to the undermining of Brazilian democracy. On the contrary, they have systematically disregarded their constitutional role by engaging in partisan politics and taking up civilian positions in the federal administration.

Bolsonaro’s sect of fanatical supporters seem to want Brazil’s far-right president to be the country’s absolute ruler even without the need for elections, following a distorted interpretation of the constitution. The military at least pretended they wanted elections to be held, but did not hesitate in joining the president’s chorus of electoral fraud.

Preparing the ground

In October 2022, Bolsonaro faced a resurgent Lula in the presidential election. Anticipating defeat, the incumbent president spent months sowing suspicion over the voting machines and questioning the integrity of the electoral process. Bolsonaro’s loss by a thin margin after a run-off ballot was enough for him to refuse to concede. Large numbers of his 58 million voters followed suit.

Bolsonaro’s silence for the two months between elections and Lula’s inauguration appears to have served as a nod and a wink to rally his supporters, who blocked roads, threatened political opponents and built camps in front of army barracks, all the while calling for military intervention. Days before the inauguration, the president fled the country, flying to Florida, suggesting that his life was at risk in Brazil. His supporters seem to have interpreted this as a call to action.

With this background, it was just a matter of time before the Brazilian version of the January 6 US Capitol riot took place. It seems that coup-mongers decided to act after Lula took office and counted on the complicity and negligence of Brazil’s armed forces and state security.

It was both embarrassing and shocking to see police officers calmly sipping coconut water while protesters stormed into Brasília’s main public buildings. Army soldiers who should have been securing the presidential palace did nothing as criminals destroyed or stole works of art, furniture and government documents.

Swift response

Lula’s response has been swift. He issued a decree establishing a federal military intervention in Brasília to stop the chaos, which has so far been responsible for the arrest of over 1,500 rioters. We are also witnessing unprecedented coordination between executive and judiciary branches to investigate who is behind the attacks on Brazilian democracy.

For Lula, it will now be crucial to identify and clamp down on the members of this violent far-right network. This does not mean only those who invaded the buildings, but also the people that funded them, who incited the protests and who created the narratives responsible for the coup-mongering of recent years.

If Lula’s mission is to bring the country together again, his administration must ensure that Brazil will no longer serve as a laboratory for extremist tactics and ideologies as it did over the past few years.

Bolsonaro, meanwhile, remains in hospital in Florida after complaining of intestinal pains related to a stabbing he suffered during the 2018 election campaign. He may have distanced himself from the storming of the government buildings. But now the discussion will focus on whether – and when – he will return to Brazil and, if he does, whether he will face charges of inciting insurrection.

Guilherme Casarões is a professor of Political Science at São Paulo School of Business Administration (FGV/EAESP)

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article here: https://theconversation.com/brazil-insurrection-how-so-many-brazilians-came-to-attack-their-own-government-197547