After Dilma Rousseff was ousted as president in August 2016, Brazil’s pro-impeachment camp confidently proclaimed that “the institutions are working”.

Rousseff was accused of disguising shortfalls in the government’s accounts – though some fretted that it was a weak basis for ousting a leader in a presidential system, the impeachment process was procedurally rigorous.

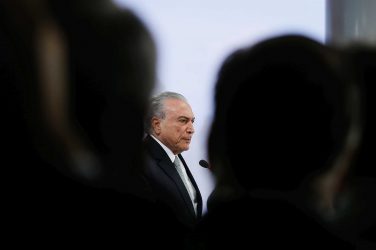

But only a few weeks into the tenure of Rousseff’s substitute, Michel Temer, her camp enjoyed something resembling revenge. Corruption allegations against supporters of Temer’s government quickly emerged, leading to the replacement of five ministers in the first six months.

Rousseff’s defenders didn’t miss a beat: “The institutions are working!” they declared, with the irony turned up to full. Not that they admitted any wrongdoing on their side; rather, they were denouncing the corrupt politicians who had posed as guardians of the constitution while voting to impeach Rousseff.

And so it continues. Former president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who orchestrated Rousseff’s election in 2010, has now been sentenced to almost a decade in prison for corruption and money laundering.

He can still appeal the decision, but his chances of avoiding prison time are slim. What does all this say about judicial institutions and the future of politics in Brazil?

First, a recap on the ongoing corruption scandal. “Operation Car Wash” is a colossal investigation into a kickback scheme centered around Petrobras, the national oil company.

The scheme was organized by government-appointed managers in the firm, who colluded with a cartel of contractors. Bogus bidding rounds led to massive over-invoicing, with part of the money returning to the fraudulent managers.

Much of this cash was apparently siphoned off to the secret coffers of political parties, including Lula and Rousseff’s then-ruling Worker’s Party (PT).

Since 2014, the operation has produced 157 convictions, and issued more than 1,500 years of prison sentences. Of the roughly US$ 12 billion prosecutors are trying to recoup, about US$ 234 million have already been recovered from offshore accounts. Billions of reais in fines are being paid by just two giant companies, Odebrecht and its affiliate Braskem.

Yet, while Operation Car Wash is extraordinary in its proportions, it’s not entirely novel. In fact, the structures needed to support such a colossal investigation have been under construction for a long time.

Built to Last

Brazil’s anti-corruption mechanisms have been incrementally improving ever since the return to democracy in the late 1980s. The country boasts a highly professional civil service, including increasingly well-funded and trained public prosecutors, supported by the equally competent Federal Police.

It also benefits from a vibrant and demanding civil society, as well as fierce competition among political parties. This is far from an unhealthy system, and the independence and strengthening of anti-corruption institutions is a testament to how far Brazil has come since democracy was reinstated.

Still, when it comes to the political implications of the crackdown, Brazilians are divided. The traditional center-right is mostly reassured that the country’s institutions are functioning as intended, at least to the extent that corrupt politicians are being prosecuted.

It helps that the focus is specifically on Petrobras, a state-controlled company that economic liberals consider not only corrupt but also highly inefficient.

But predictably, they’re less enthusiastic about accusations leveled against politicians from the now-ruling center-right. They’d rather press on with the Temer government’s planned reforms, which they see as a chance to return to the liberalizing project of the Cardoso presidency (1994-2002), and as essential for future solvency.

The mainstream left, on the other hand, is highly suspicious of Car Wash, which it regards as a partisan effort to undo the progress on welfare policy since the PT came to power in 2003. However, this is also in part a panicky reaction to the effective destruction of the PT’s preeminent position.

Despite improvements in the functioning of the state, Brazilian political parties are not, in themselves, the strongest of institutions. They depend heavily on charismatic leadership, rather than robust internal procedures to elect party candidates and leaders.

The downfall of Lula will therefore drastically weaken the PT, which has so far not signaled any serious internal effort to renew its leadership or distance itself from past mistakes.

Work to Be Done

A growing contingent of young Brazilians are demanding neither more nor less government, but better governance. This is directed at all those in power across the political spectrum, a culmination of earlier demands from both the left and right.

The issue that all parties now face is that it has become politically inconceivable to drastically alter the country’s current macroeconomic model, or to scale back robust investments in welfare, the forces that created Brazil’s young, informed and aspirational middle class.

That group is broadening and solidifying – and its attention is duly turning to both the quality of service provision and the conduct of national leaders.

The lead Car Wash prosecutor, Deltan Dallagnol, personifies this new Brazilian mindset: a fervent Baptist wielding a degree from Harvard Law School, he is 37 years old and has no time for traditional Brazilian patronage systems, whether in everyday life or in the upper echelons of politics.

But while this might look like a deadlock between the status quo and the future, in fact, it’s typical of the way the country works. Political scientists argue that in Brazil, policy changes “through accretion, rather than substitution” – that reforms aren’t contested, overturned and replaced with others, but simply layered on top of each other.

So while the liberal macroeconomic orthodoxy entrenched in the 1990s remains in place, so does the wealth redistribution project that came to fruition in the 2000s. The country has now reached another juncture, one where systemic corruption and inefficiency are no longer tolerated.

The Car Wash metaphor is highly apt: Brazilian leaders are being compelled to clean up their act and reform the system that has protected them for years.

It remains to be seen just how long the myriad investigations will take, and whether they will be constrained by politics – there’s no knowing how much the fallout could damage the economy or whether the political system will be properly reformed, especially when it comes to campaign finance.

Most crucially of all, the archaic and undemocratic internal structures of Brazil’s umpteen political parties must be challenged and dramatically upgraded. Only once these things are achieved will a desperately needed new generation of national leaders start to emerge.

Felipe Krause is a PhD Candidate in Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original article here: https://theconversation.com/lulas-conviction-proves-brazil-is-strong-enough-to-reform-itself-80979