Behind a heavy metal gate and walls painted with murals of revolutionary icon Che Guevara, stands a farmhouse occupied by Brazilian squatters as part of a movement to turn abandoned buildings into affordable housing.

With operations run from the farmhouse, the Homeless Workers Movement (MTST) is one of Brazil’s most influential housing rights organizations, with around 50,000 members coordinating more than 30 occupations across São Paulo.

Their strategy is straightforward: occupy abandoned buildings and under-used land to pressure the government to negotiate and eventually build affordable housing for squatters.

To their critics, the MTST and their rural sister group the Landless Workers Movement (MST) are little more than well-organized thieves usurping other people’s property to further their leftist political ambitions.

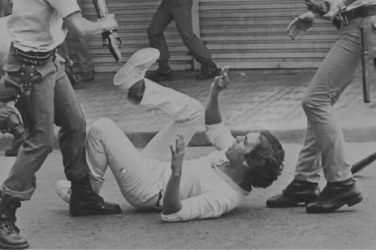

Government officials, including the Public Security Department of São Paulo, accuse the groups of “inciting violence and disobedience” during their housing protests.

Supporters say the group is making concrete progress to provide the urban poor with a place to live.

With homelessness rising across Brazil as it suffers its deepest recession since the 1930s, MTST has promised to step-up its occupations.

“Private property is a right, but it has to serve the public good,” Jose Alfonso da Silva, 46, an MTST campaigner told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“If buildings are abandoned by real estate companies or speculators, if they are being used as spaces for crime, then they should be given to someone who uses them productively.”

The farmhouse turned campaign headquarters in Taboão da Serra, a gritty suburb 20 km (12 miles) west of central São Paulo, was once one of those abandoned buildings.

Activists occupied it in 2007 and the government eventually allowed them to stay, Alfonso said, drinking sweetened coffee from a plastic cup and smoking a cigarette.

In greater São Paulo alone, a megacity of 20 million people, there are about 1.2 million abandoned homes – more than enough to help residents who don’t have a decent place to live, said Alfonso.

Brazil faces a deficit of about 7 million homes, according to data from the U.S.-based Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

This deficit has expanded in recent years despite the government building more than 2.6 million low cost homes since 2009.

Part of the reason for this problem stems from rapid migration from the countryside to cities, said Marieke Riethof, a lecturer in Latin American politics at Britain’s University of Liverpool.

“Cities have expanded far beyond their capacity,” Riethof told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“Part of the agenda of the MTST is to regularize some of the irregular areas (on the fringes of cities) to make them more suitable for communities.”

Backers of the group say they have won concrete victories securing housing for poor city residents who are priced out of the real estate market.

“I am able to live here thanks to the movement,” said 73-year-old retiree Joseph Ferreira da Silva, looking up at his two bedroom apartment close to the MTST farmhouse.

His home, and 300 others in a collection of concrete apartment blocks, were built with public money following an occupation of the land on which they stand.

“I like living here better than my place before, I’m happy,” da Silva said in the parking lot of the gated development. “We never would have gotten this housing if we hadn’t protested.”

Residents like da Silva have formal title deeds to their properties and access to public services built as part of the project.

Formal Vs Informal

Traditionally, Brazil’s urban poor have moved onto vacant land and built their own houses in communities known as favelas with whatever materials they could find, said MTST’s Alfonso.

In large cities like São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, more than 20 percent of the population live in favelas, according to government data.

These communities, however, often do not have public services like sewage, running water or formal property ownership deeds, which can give residents a greater sense of permanence.

“The problem is that people can be evicted,” Alfonso said. “We fight so land is used for public housing with dignity: education, health facilities and sports fields.”

The neat, new apartments where da Silva lives, for example, stand in contrast to the surrounding favelas of crumbling brick homes and webs of illegally-erected electrical wires.

After the MTST occupies land or buildings they negotiate with authorities to build new housing on the site based on what local people say they want.

“Their strategy includes the participation of families so they can indicate what they need in terms of housing,” said Riethof, the politics lecturer.

“Their high profile occupations draw attention to inequalities in property distribution, and make housing policy more participatory,” Riethof said.

Brazil’s government says it’s working to regularize informal communities by providing better public services and property titles, although budget cuts due to the recession have hampered the effort.

“Inspection measures will be improved to avoid irregular occupations,” Emerson Figueiredo, a spokesman for the City of São Paulo told the Thomson Reuters Foundation without commenting specifically on the MTST’s politics.

The government is planning to build another affordable housing complex for hundreds of residents close to da Silva’s apartment block, Figueiredo said.

The city government needs an agreement between MTST occupiers who are living in the area, and the land’s private owner, he said.

This article was produced by the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Visit them at http://www.thisisplace.org